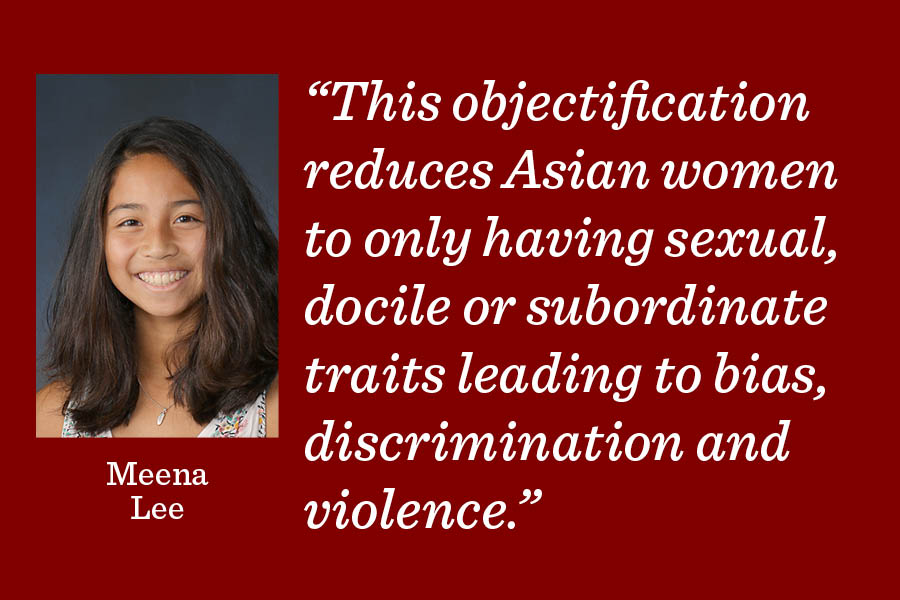

Deconstruct the fetishization of Asian women

Midway staff

This hate crime exposed the intersection of misogyny and racism that Asian women face and sparked necessary conversations about the importance of deconstructing the fetishization of Asian women, writes content manager Meena Lee.

April 23, 2021

On March 16, I opened my phone to the headline: “Eight Dead in Atlanta Spa Shootings.” As I continued to look into the news I saw more headlines like, “Six of the eight victims were women of Asian descent.” Immediately, I attributed the shooting to the anti-Asian bias that has been on the rise since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. However, as I read more, I noticed the bias was even more deeply rooted.

It was reported that the shooter told police he had a “sex addiction” and had targeted these spas in order to get rid of his “temptation.” This hate crime exposed the intersection of misogyny and racism that Asian women face and sparked necessary conversations about the importance of deconstructing the fetishization of Asian women.

The portrayal of Asian women in the media is rooted in colonization and further promotes sexual stereotypes. This objectification reduces Asian women to only having sexual, docile or subordinate traits leading to bias, discrimination and violence.

If they are ever discussed, Asian fetishes are often spoken about in a very casual way. However, there is a long history of American legislation and media that have connected Asian women with sexualization, and understanding this history is an important part of unlearning.

In the 1850s, an influx of Chinese immigrants to the West Coast led, unsurprisingly, to an anti-Chinese sentiment, which grew as immigrants were perceived as a threat to the racial purity of white America. Chinese women in particular were perceived as a sexual threat. They were stereotyped as prostitutes and accused of spreading sexually transmitted diseases. This scapegoating of Asian people in relation to disease demonstrates an eerie parallel to today with the coronavirus pandemic.

Then, in 1875, the Page Act was passed. Seven years before the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Page Act was designed to outlaw “the importation of women for the purposes of prostitution.” In practice, it left an individual’s immigration to be decided by the consul at port cities and was used to restrict the immigration of all Asian women. This furthered the stereotype of the connection of Asian women to sex work.

Additionally, the strong presence of the U.S. military in Asian countries in the 1900s has contributed to many tropes of Asian women’s bodies existing for American soldiers. These tropes were popularized through productions such as “Madame Butterfly” and “The Toll of the Sea,” which created both hypersexual and docile representations of Asian women. These stereotypes are continually found in the media today. For example, the anime industry portrays hyper sexualized Asian women. While it is predominantly made by Japanese creators, it has been consumed readily by Americans.

Returning to the Atlanta shootings knowing this history, the problem becomes even more strikingly evident. The issue has been recognized on the national level, with the Senate passing an anti-Asian hate bill on April 22, but that is just a start to combatting the systems of racism that Asians face in America. The mere statement that the victims were “temptations” for the shooter highlights the need for everyone, regardless of race or gender, to examine who they are attracted to and what media they consume in order to deconstruct fetishization.