Strategies & solutions for safety

February 10, 2022

Addressing the gun violence epidemic in Chicago requires approaches beyond increasing law enforcement. To aid neighborhoods affected by divestment and generational trauma, the University of Chicago has announced its intention to partner with community organizations that provide trauma recovery, behavioral therapy and access to employment. University research groups are seeking to identify effective strategies to reduce crime. Meanwhile, Lab students continue to stay on alert while walking home after school.

Partnership targets gun violence at its root

In a roundtable discussion on Jan. 25, University of Chicago President Paul Alivisatos reiterated the university’s commitment to partner with community organizations to address gun violence in Chicago following the deaths of two university students and a recent graduate in 2021.

Although the Department of Safety and Security has recently announced efforts to enhance university law enforcement and expand the Lyft Ride Smart program, Dr. Alivisatos underscored the importance of addressing root issues such as divestment, educational inequity, generational trauma, and lack of access to mental health services in the community.

“As an university we are committed to contributing our strengths and research and education and our resources to work in partnership with the community and the city to work toward common solutions urgently needed to address this most critical of issues,” Dr. Alivisatos said during the discussion.

He announced the university’s new initiative to issue grants funding partnerships between members of the university and community organizations. The funding will target areas such as social and economic pathways, trauma recovery efforts, reentry initiatives, community police relations and understanding why certain violence prevention programs are effective.

Some initiatives affiliated with the university to improve public safety have already proven to be effective. These include the UChicago Justice Project, UChicago Medicine’s Violence Recovery Program, Trauma Responsive Educational Practices project, Choose to Change, and READI Chicago.

Launched in 2015, Choose to Change provides six months of wraparound services and cognitive behavioral therapy to teenagers in the south and west sides of Chicago. During therapy sessions, teenagers learn to regulate themselves during high stress situations. As part of the wraparound services, mentors from similar communities build relationships with the participants, identify their interests, and help them form plans to pursue those interests.

“Any barriers that will prevent them from completing their education, we try our best to eliminate those barriers and support families and meet them where they are and give them the support that they need,” said David Williams, Midwest region vice president at Youth Advocate Programs.

Another program utilizing cognitive behavioral therapy is READI Chicago. Under a different model, READI Chicago combines therapy with providing employment opportunities and support services in areas such as Medicaid, housing, mental health and substance abuse. The 12-month program targets men in the North Lawndale, Englewood and Austin-West Garfield neighborhoods.

According to Senior Program Manager Nyzera Fleming, the structure of the program allows participants to learn socioemotional skills in the classroom and then apply those in real-world situations.

“In a setting where your supervisor may say, ‘Hey, I need you to go from this task to the next task,’ they’re being coached on how to handle those situations or, you know, be able to take feedback or be able to know those basic standards of HR as it applies to, you know, sexual harassment or how to handle anger management and things of that nature,” Ms. Fleming said.

The Urban Labs Crime Lab at the University of Chicago has rigorously evaluated Choose to Change and READI Chicago. Researchers compared participants of these programs with peers of similar backgrounds. Compared to their peers, teenagers who participated in Choose to Change were 48% less likely to be arrested for violent crime, and they attended seven more days of school. Men who participated in READI Chicago were 79% less likely to be arrested for shootings and homicides compared to their peers.

In the round-table discussion, Deborah Gorman-Smith noted that even with new public safety initiatives, there will likely be no changes in the next three or five years.

“We’ve demonstrated really importantly that prevention works,” Dr. Gorman-Smith said during the discussion. “We can do things to decrease risk for violence, but we haven’t concentrated those efforts in a way that makes real progress in reducing community level rates of violence.”

Research informs safety initiatives

In 2007, University of Chicago Ph.D. student Amadou Cisse was shot and killed on campus. Fourteen years later, UChicago graduate Shaoxiong “Dennis” Zheng, rising third-year student Max Lewis and Ph.D. student Yiran Fan similarly died from gun violence in 12 months, sparking a need for researchers to help resolve the issue of gun violence.

Programs at the University of Chicago are trying to better understand the source and the steps needed to take to prevent future incidents of gun violence.

The University of Chicago Crime Lab was launched in 2008 and partners with the public sector to use research to test and evaluate programs that enhance public safety. They are involved in assessing numerous programs like the READI Chicago, a program that works to connect men with the highest risk of experiencing gun violence with the resources they need.

“I think one challenge is that there is this sort of perception, that all sorts of crime are up everywhere,” said Roseanna Ander, executive director of the University of Chicago Crime Lab. “It’s not all types of crime. It’s gun violence that has increased very, very sharply.”

According to Ms. Ander, the burden of the gun violence crisis is disproportionately concentrated in certain Chicago neighborhoods, particularly among specific groups within those neighborhoods.

“I think, you know, people talk all the time about equity. If we’re going to actually be serious as a city about equity, then we need to understand where the burden is greatest, and where the needs are the greatest and devote the needed resources equitably,” Ms. Ander said. “And so I think it would be important for the university, but you know, all parts of the city government and philanthropy and others that have resources to take seriously this notion of equity.”

According to Ms. Ander, the University of Chicago should think about employment opportunities for residents of Chicago, prioritize residents to create job opportunities and continue to ensure that high-quality research can be generated. In a broader scope, Ms. Ander believes the criminal justice system needs to be more effective when it comes to gun violence and reform.

“We need to focus on not having the criminal justice system involved in things that actually aren’t really public safety issues,” Ms. Ander said. “So, you know, things like low-level arrests for substance use is an example of things that the criminal justice system gets involved in, that probably isn’t really providing much public safety benefit, and probably creating real harm.”

She expressed a need for more infrastructure to provide opportunities for individuals who were previously incarcerated or involved in violence to feel included in society.

“When you look at who’s being victimized by gun violence, and who are the individuals who end up getting arrested for gun violence, the average age is something like 27,” Ms. Ander said. “We do not have anywhere near the infrastructure that is designed to serve that population.”

Myles Francis, project manager of the Chicago Center for Youth Violence Prevention, is working directly on these issues and hopes to see more funding opportunities for programs that approach violence from a community and trauma-informed perspective.

“We need to identify the people that are trying to do the work, trying to do street outreach and trying to tackle food insecurity,” Mr. Francis said. “We also need to provide the funding necessary to connect those people and to give them the tools needed to implement their violence interventions at a high level and to evaluate them rigorously.”

Mr. Francis said the University of Chicago needs to do a better job of listening to the opinions and suggestions of the community and incorporating them when taking action.

“The university has so many talented people, and so many resources, and so much access and so much money,” Mr. Francis said, “and it owes a lot of that to the communities that surround it.”

According to Mr. Francis, Hyde Park and the areas that surround the university present a unique challenge to public safety due to the “bubble mentality” it possesses.

“Hyde Park is a space where it seems like there isn’t a full commitment, not from the community so much as the large power-wielding institutions, to address violence in a way that reflects how close they are to it,” Mr. Francis said. “There is a community of people that would very much like to operate as if Hyde Park is downtown and doesn’t have to engage with or worry about the violence that neighboring communities have to deal with.”

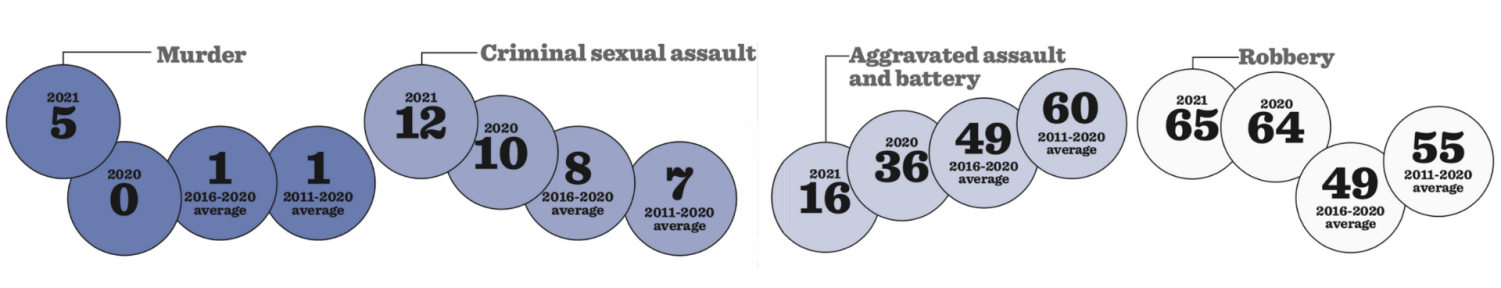

By the numbers

The following data from the Chicago and University of Chicago police departments illustrates the number of incidents of murder, criminal sexual assault, aggravated assault and battery, and robbery in the Woodlawn UCPD Patrol Area. The area spans from 61st to 64th Street, Evans to Stony Island Avenue, and Ellis to University Avenue. The onset of the pandemic in March 2020 was one factor influencing the rate of violent crime in the past 10 years.

Students keep up awareness

Walking home or to a car after a day at school has become a little more complicated recently.

While students say they don’t feel unsafe around school, safety concerns in Hyde Park such as the fatal shooting in December of Shaoxiong “Dennis” Zheng have prompted some to utilize additional strategies for safety and increased awareness of their surroundings.

Issues with safety haven’t changed the activities that senior Alp Demirtas enjoys, but they have caused him to take extra caution while walking around.

“I still, like, go out downtown and go out in Hyde Park and do all those things,, but I just always remain vigilant because you never know what might happen,” said Alp, a Woodlawn neighborhood resident. “I always look around me just to make sure I’m not being followed, make sure to keep my phone out of sight.”

Alp said he and his parents have a couple ways to make sure he stays safe, such as phone tracking and a curfew, although they started well before the most recent safety concerns in Hyde Park.

“My parents just want me to come home before it’s dark,” Alp said. “They’re also able to see where I’m at and my location and stuff, so that kind of helps ease things.”

Senior and Hyde Park resident Jonah Schloerb, who lives near Promontory Point, said he often walks home after dark. According to Jonah, more street lights and blue-light systems may help ease concerns of students.

“Having more street lights everywhere just so everything’s lit up and those blue-light things on the street corners that you can push the button of,” Jonah said. “Those help me feel more safe.”

After dance troupe practice, junior Ishani Hariprasad drives herself home in the Kenwood neighborhood. With the recent frequent security notifications from the university, she is more careful.

“Walking to my car when it’s darker after dance practice, I usually walk with somebody, like one of my friends,” Ishani said.

Ishani said the security alerts are a topic of concern in her family.

“Every time my dad gets one of the emails, he forwards it to me and my sister, and she’s at the university,” Ishani said. “Once I leave the house in the morning, he and my mom both ask me to text them when I get to school and, like, vice versa when I leave.”

Hyde Park junior Anna Bohlen lives only half a block from school, and while she said she usually feels safe walking home, there are times when she’s uneasy.

“I definitely watch my surroundings more, and if it’s dark out and there’s someone on the street, I watch them carefully, just in case,” Anna said. “I don’t think my parents feel fully comfortable with the idea of me walking home in the dark, but they’re OK with it since I live so close.”