Fact or Fiction: Determining truth from falsehood

October 7, 2021

One of the primary issues of the digital age is determining truth from falsehood. Skills of reasoning and media literacy have become more relevant than ever before.

Stop, think it through

Rapid scientific research leading to the rise of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines against the coronavirus accompanies a simultaneous spread of misinformation and disinformation. Just 12 influencers, termed the Disinformation Dozen, are responsible for up to 65% of anti-vaccine content. While evidence debunks claims that messenger RNA vaccines change DNA, cause autism, or render people infertile, false information continually fuels vaccine hesitancy and impedes progress toward herd immunity.

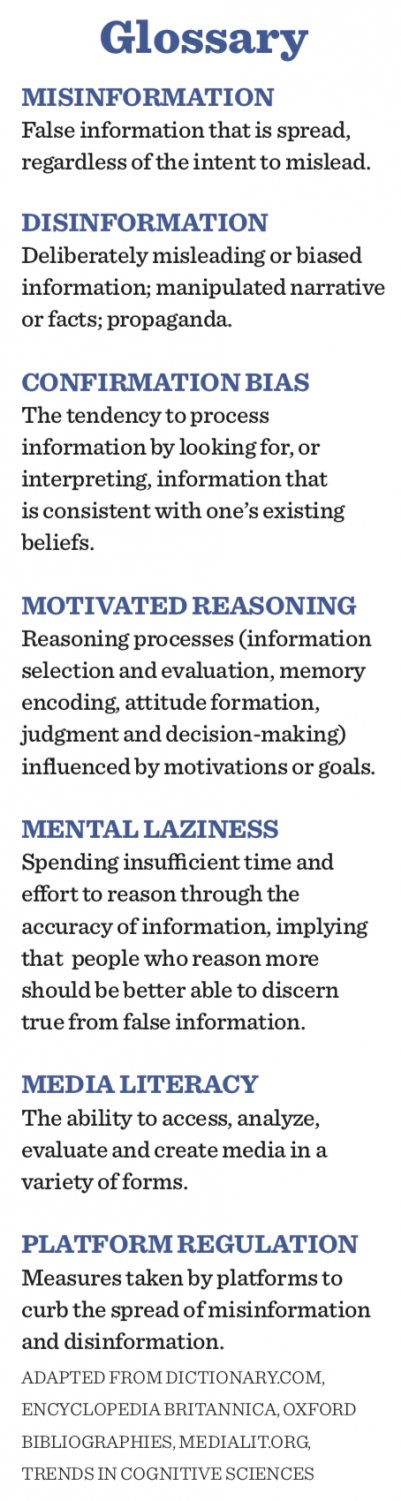

Misinformation is false information, spread regardless of intent. Disinformation is false information, spread with the intention to deceive. The impact of misinformation and disinformation extends far beyond the coronavirus.

“I think misinformation and disinformation both have undermined America — not just America, the world, the world’s trust in institutions, in science, in democratic processes — because they’ve raised so much doubt in people’s minds,” Darren Linvill, associate professor at the Clemson University College of Behavioral, Social and Health Sciences, said in an interview.

Why do people believe misinformation?

Two concepts from psychology come into play, according to Deen Freelon, associate professor at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. One is confirmation bias, believing ideas that fit with one’s preexisting beliefs, and the other is motivated reasoning, actively reasoning to fit new ideas into one’s preexisting beliefs. The combined effect of both concepts makes it difficult to discern facts from false statements aligning with preexisting beliefs.

“The fundamental issue is that often, disinformation and misinformation is targeting groups of people that are already inclined to believe that information,” Dr. Linvill said. “Often that’s because it’s coming from sources that they trust, that are part of their social network, people that purport to have the same identity as they do, and oftentimes identity is more important than facts.”

At the same time, other researchers, including David Rand and Gordon Pennycook, suggest that mental laziness rather than motivated reasoning is the primary issue affecting judgement of accuracy. Their evidence indicates that people who spend more time reasoning about the accuracy of information are better able to discern fact from fiction. A nudge in a social media post questioning the truth in content may be sufficient to bring people to consider the accuracy of information.

The issue of misinformation is often more than the difference between fact and fiction. Even with accurate supporting facts, a writer’s language may be laced with an agenda, according to history teacher Cindy Jurisson. For mainstream newspapers like The New York Times and Chicago Tribune, the interest of maintaining a business comes at odds with the publication’s function as a democratic watchdog.

“It’s tone. It’s use of certain kinds of words that may have more of a pejorative cast. It’s adverbs or adjectives that appear to be sort of neutral but actually sort of fulfill a certain agenda,” Dr. Jurisson said. “There’s a lot of that to go around, and I wince when I see it even in publications I trust more because you don’t want that to leak too much into hard news.”

She said that part of her goal as a history teacher is to impart close reading skills to her students. Close reading entails maintaining a skepticism toward the content, questioning claims for evidence and even reading correction pages to observe how publications address inaccurate reporting.

“Trust but verify — not cynical,” Dr. Jurisson said. “I don’t think we should be cynical, but reading with a healthy skepticism is really important when we’re consuming news about public events.”

Whether belief in misinformation stems from motivated reasoning or mental laziness, discerning true statements from false ones takes time and effort. Senior Kennedi Bickham said it is often not practical to double-check claims in assimilating the mass amount of information presented by outlets each day.

“I do not have the effort to actually seek out the information and check if it’s true. Just because, unlike those types of sites, you’re just scrolling for entertainment, so if you see something that’s fake, or you suspect of being fake, but it’s kind of funny, you’re just gonna keep laughing, keep rolling.”

It’s coming from sources that they trust, that are part of their social network, people that purport to have the same identity as they do, and oftentimes identity is more important than facts.

— Darren Linvill, Clemson University

Solutions to curb misinformation come from both the supply and demand side, according to Dr. Freelon. On one hand, platforms can regulate the content they present and take down misinformation accordingly. Youtube banned content spreading coronavirus misinformation on Sept. 29. On the other hand, users can learn media literacy or simply take more time and care to consider the accuracy of information they consume.

“When you are reading media or consuming media, from any source to the political side of the spectrum that you’re on, that’s when you’re most vulnerable to falling for mis-or disinformation,” Dr. Freelon said, “so you have to be extra careful with that kind of content.”

Stopping the spread of misinformation likely requires both supply and demand side solutions.

Misinformation solutions rely on regulation, media literacy

Misinformation continues to threaten the communication of reliable information, but mitigating its spread will require people to be more diligent and platforms to regulate the content they permit.

Although the dissemination of misinformation is sometimes unintentional, it has repercussions on the general public and especially people who are impressionable like children.

Everyone should take measures to ensure that a resource, article or message is accurate. Taking the caution of increasing skepticism and fact-checking sources are crucial steps to preventing the spread of misinformation.

Anita Rao, a professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, said that regulation is a key component of halting the spread of misinformation. She is an empirical marketing researcher who observes the way in which consumers react to deceptive advertising.

“Consumers should be more skeptical when hearing things that seem too good to be true or really anything in general,” she said. “But really beyond that, we need some kind of regulatory body who is doing the research for us.”

Dr. Rao referenced the Food and Drug Administration as an example of a regulatory agency which has the power and credibility to check the legitimacy of certain drugs and prescription medications. She said a way to apply this idea to more conventional information consumption is prioritizing “.gov” and “.edu” as opposed to “.com” sites when doing research. Additionally, utilizing impartial sources such as the New York Times is key.

Dr. Rao emphasized the danger and inconsistency of social media and especially its effect on the younger generations.

According to a 2018 study conducted by professors at the MIT Sloan School of Management, posts containing dishonest information were 70% more likely to be retweeted than the truth.

“My personal solution, and one I suggest to all, is just not to look at social media for information. Instead, look at facts. Though facts may be more difficult to digest, you know for sure whether or not the information is trustworthy or not,” Dr. Rao said.

Similarly, Zizi Papacharissi, a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago who serves on the editorial board of 15 journals, said that becoming more aware of the way in which people are vulnerable to propaganda is part of the solution.

“People in general can send messages — loud ones — when things are wrong,” Dr. Papacharissi said.

She suggests people should not be tempted to look at materials that seem too good to be true.

“A strong message can be sent by refusing to click on deepfake or clickbait content… [and] by refusing to consume content that underestimates our intelligence as citizens.”

Additionally, Dr. Papacharissi emphasized the relevance of resources such as librarians as almost all libraries have solid guides for fact checking.

“How to prevent misinformation — that’s the million-dollar question,” Dr. Rao said. “It is really a matter of being smart and using reason when deeming a source to be credible or appropriate to spread.”

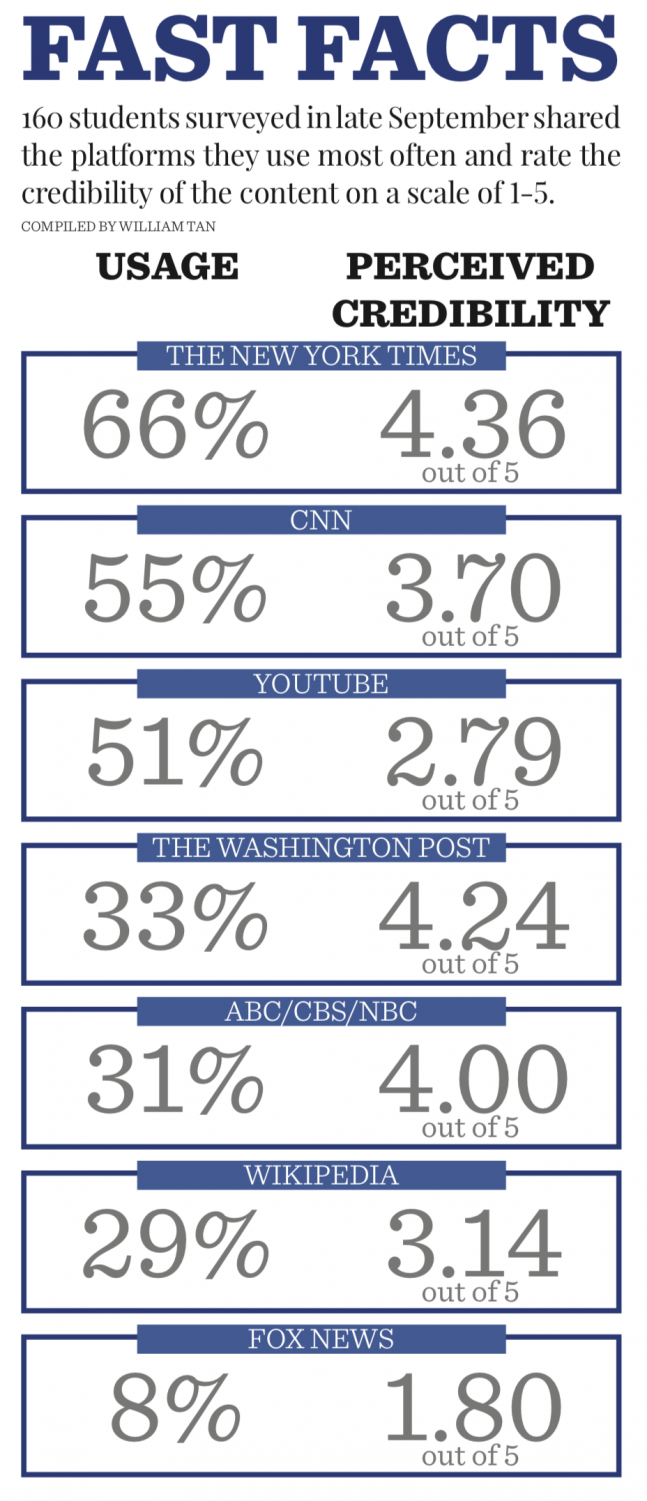

Misinformation fast facts

False claims spread vaccine distrust, promote hesitancy

Celebrity and singer Nicki Minaj tweeted on Sept. 13 to her 22.8 million followers a claim that a distant acquaintance was rendered impotent due to the COVID-19 vaccination. Ms. Minaj wrote that one should “just pray on it & make sure you’re comfortable with ur decision, not bullied.” The message divided Nicki Minaj’s fanbase and spilled over to the rest of the online world, calling into question the line between outright misinformation and the sharing of a personal anecdote.

Ms. Minaj’s claims were proven to be unfounded, and there has been a large amount of backlash to her tweet. However, anti-vaxxers and fans of Ms. Minaj still work to defend her. A small number of people believe that the vaccine is entirely harmful and should not be taken by anybody, but the majority of Ms. Minaj’s fans defend her on a different basis. In her tweet, she never explicitly said not to get the vaccine. Her fans argue that she was simply sharing a personal experience.

Twitter user @Shenekaaa argued in defense of Nicki Minaj, writing “She and any other person in this world is allowed to share their experiences. How you decide to twist and interpret it is on you.”

However, a different sentiment exists at the Laboratory Schools. Many students are upset or disappointed in Nicki Minaj, believing that her simply sharing the story is irresponsible as it spreads misinformation and encourages hesitation toward the vaccine. While she did not directly suggest not getting vaccinated, junior Nathan Greeley said he believes Ms. Minaj’s tweet is almost as bad.

“I thought it was funny at first, and then I realized it wasn’t ironic,” Nathan said. “She could just be really really stupid and is not seeing how extremely harmful this could be to people.”

Vaccine hesitancy has been proven to be a legitimate and growing issue, and no matter Ms. Minaj’s original intent with her tweet, it inspired hesitation in some of her 22 million followers.

The user @Tasty_MINAJ wrote on Twitter, “I had to get the vaccine cause they wouldn’t let me look for a job or get a job and to earn some money, and now im unsure about getting the second vaccine.”