Best and worst of page to screen: Some film adaptations miss target

Random House and Illumination Studios

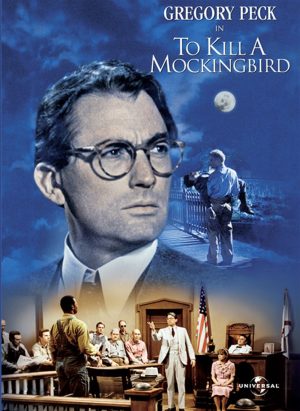

Movies like “To Kill a Mockingbird” support the integrity of the books they are based off of. The movie is able to condense the book’s plot while keeping its strong themes.

“The Lorax,” “To Kill a Mockingbird” and “The Lord of The Rings” movies don’t have much in common, but they all share the same origin: they’re adaptations of popular books. Some adaptations elevate their source material while others fall flat and smudge their books’ legacy. These three books show the range of how adaptations can succeed and fail.

“The Lorax”

“The Lorax” movie is fun. It has an entertaining plot and well-constructed characters, but in the shadow of the original book, the movie is a disappointment.

The impact of “The Lorax” book stems from the story’s simplicity. Its message is powerful and focused. Without the freedom to leave details off the page, the movie cheapens the intended message.

In the book, the child who listens to the Once-ler’s story is addressed as “you” and the Once-ler himself is never fully shown. The kid listening to the Once-ler is meant to be you, the hypothetical reader of the book. The Once-ler is faceless because he represents the many faces of older generations who harmed the environment. These choices are made poignant because “The Lorax” is a picture book: a story often read by parents or teachers to young children. The adults take on the role of the Once-ler, telling the story of their mistakes to the children who will inherit the world.

In the movie, “you” is replaced by a character named Ted Wiggins and the Once-ler has a face along with a fleshed-out backstory. The Once-ler has a demanding family that pressures him into making his reckless decisions, and Ted only wants to learn about trees to impress his crush. Ted often appears naïve and stupid, while the Once-ler seems sympathetic. These two changes are antithetical to the book’s intent.

The “thneed,” an amorphous representation of meaningless capital in the book, is presented in the movie as a spoof mixture of a Snuggie and a Sham-Wow. The Truffula Trees that represent nature and define an ecosystem in the book, are simplified to an ascetic in the movie.

While the book spreads a message about environmental decay, capital culture and hope for the future, the movie presents a muddled cynical message about decaying human nature, corporate surveillance and despair. “The Lorax” book simply wasn’t built to become a movie.

“The Lord of The Rings”

“The Lord of The Rings” movie adaptations successfully build off of the source material, respecting the invested audience while welcoming new viewers.

The secret of the adaptation’s success is J.R.R. Tolkien’s intricate storytelling and world-building ability. Tolkien is known for his almost arduously descriptive scenes and intricate complex lore. His detailed writing provides extensive guidelines for a visual interpretation of the text, making the film adaptation satisfying for fans of the books.

The movies cater to the books’ fanbase by including subtle details in the films that reference context that’s only in the novels. By including details like evidence of the events of the Hobbit in the films’ scenery and adding elvish inscriptions on props, the movies respect the books and the fanbase they cultivated. The references aren’t distracting and, because the story follows a mostly straightforward plot, first-time viewers don’t get lost.

This balance is exemplified by the choice to create a director’s cut of the films. Dedicated fans of the books can watch a longer version of movies that include details that the director, Peter Jackson, thought would be satisfying for fans, but confusing or boring to the general audience.

Every part of the adaptations were clearly meticulously planned. The shooting locations, the groundbreaking special effects, the intricate props, and the epic score all show incredible thought and effort as well as a heft budget, culminating into a breathtaking love letter to the fantasy genre.

Tolkien’s “The Lord of The Rings” books were perfectly suited to transcend their medium, and the films delivered on that potential by sparing no expense in faithfully recreating the epic world created in the novels.

“The Lord of The Rings” franchise pulled off one of the most successful translations of a complicated fictional world from text to movie theaters by working to maintain the complexity of Tolkien’s masterpiece.

“To Kill a Mockingbird”

The movie adaptation of “To Kill a Mockingbird” is widely recognized as one of the best film adaptations of a classic novel. The movie brilliantly condenses 281 pages into two hours and nine minutes of film without feeling rushed or hollow.

“To Kill a Mockingbird” can be distilled without jeopardizing the integrity of the story because the story presents an idealistic and uncomplicated narrative. That simplified narrative is believable because the story is portrayed from the perspective of a child. Full characters and major plotlines are completely absent from the movie adaptation, but those details were never necessary for the execution of the basic main plotline.

Instead of exploring a more comprehensive plot, the movie focuses on thoughtfully depicting the novel’s characters. Award winning performances from actors Gregory Peck and Mary Badham do justice to the novel’s classic characters and brought the movie massive recognition. Because of the excellent acting and the simplified plot, the movie often feels more like a character study than a complex narrative.

While the book’s straightforward narrative strengthens its film adaptation, it also represents a common critique of the story. Many critics argue that “To Kill a Mockingbird’s” story oversimplifies a dense and sensitive topic. Instead of depicting and exploring racism through Black characters and culture, the plot depends on white savior archetypes. The movie extends this critique by excluding certain scenes from the book such as a moment the main characters visit a Black church and a conversation about segregated seating.

“To Kill a Mockingbird” was revolutionary for its acknowledgment of long-lasting institutional racism within the American legal system, building the foundation for later films that would go beyond acknowledgment and open complex conversations. Looking back, the movie lacks much of the nuance required to properly address such massive issues, but this lack of delicacy was an essential part of making the movie so successful and culturally impactful.