Falling into the manosphere pipeline

February 22, 2023

The “manosphere” is an online community centered around promoting toxic masculinity, often through misogynistic agitprop designed specifically to increase viewership through anger. Manosphere influencers flourish online, building audiences of millions through predatory disinformation, damaging the worldview of impressionable viewers in the process.

Creators share harmful rhetoric in online spaces

“Depression isn’t real. You feel sad, you move on… Change it.” That’s just one outspoken quote recently uttered by Andrew Tate, a name that has become household for Gen-Z teenagers. Arrested a month ago in Romania for charges of rape and human trafficking and banned from essentially every social media platform except Twitter, Andrew Tate is a controversial internet behemoth who rose to fame by touting his idea of masculinity and publicly supporting misogynistic practices.

Mr. Tate began his career as a professional kickboxer, but it wasn’t until he started posting inflammatory content on his TikTok, his podcast and his online academy called “Hustler’s University” that he became a pop culture headliner and icon — for young men. His videos about controlling and abusing women, becoming an “alpha” male, and gaining success and wealth have garnered over 11.6 billion views on TikTok. At one point his Google search interest numbers topped Donald Trump and Kim Kardashian. It’s safe to say that most adolescents surfing the internet have encountered some form of his “education.”

Mr. Tate is far from alone in his controversial philosophies. He is a member of a large web of influencers who believe in male dominance, gender inequality and sexualizing women. This community is called the manosphere, defined by the Institute of Strategic Dialogue as encompassing a range of misogynistic communities from anti-feminism to more explicit, violent rhetoric toward women.

There is a range of believers in the manosphere, but the most extreme figures think feminism is harmful to society and that all women should subjugate themselves to men, who are currently disadvantaged. Radicals like Elliot Rodgers and Alek Minassian will even resort to mass killings to realize their idea of “rebellion” — taking revenge on all women for simply existing.

A host of advocates have perpetuated the manosphere since the 1970s, evolving as a byproduct of the Men’s Liberation Movement, which began as a relative ally of feminism. After internal tension and a strange reversal, the MLA began advocating for the patriarchy and pushing for male dominance in both public and private life.

In 1996, Warren Farrell wrote the MLA’s main source of justification against feminism, the book “Myth of Male Power: Why Men Are the Disposable Sex.” During the next decade, outgrowths of the MLA such as the Fathers of Justice and Fathers Manifesto used Farrell’s work and dispersed it via sites such as 4Chan. Today, famous figures including American poker playboy Dan Bilzerian, YouTubers Steven Crowder and SNEAKO, and Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson are all embodying some part of the movement toward restoring “true” masculinity.

While its misogyny is often dispersed on social media like YouTube, TikTok and Twitter, the manosphere also functions covertly using dialectic dog whistles. Its promoters use specific language to denounce and delineate men and women in society.

There is also a spectrum of categories of manosphere men. From incels to men’s rights activists (MRA) to pick-up artists (PUA), each subgroup has slightly different views on the relationship between men and women, but all believe cisgender white males have lost their deserving place at the top of society. Members of the incel subgroup identify as victims called subhumans, people who have been dealt the worst hands in society.

Yet the manosphere extends beyond charged phrases and impassioned men arguing theories online. Concrete impacts of toxic masculinity permeate young men at local, individual levels such as reports of increased harassment in the United Kingdom and Australia, and a 2020 report from the HOPE not hate Charitable Trust, which showed in a survey that 50% of young men 16-24 believe feminism makes it more difficult for men to succeed.

The manosphere often provides a justification to explain off the feelings of insecurity and loss that adolescent males face in today’s uncertain climate: rising suicide rates (research from the Australian government supports this), a loneliness crisis due to the effects of COVID-19, and lower rates of education completion and sexual activity.

Andrew Tate will be off the internet for a while, but his legacy of misogyny has only gained greater traction since he left. As young, maturing men encounter a barrage of expectations and the need to manage tougher relationships, more and more are turning to the manosphere community to affirm their masculinity.

Gen Z must reconcile internalized bias

Like most kids my age, I grew up on the internet. My adolescence lined up roughly with the development of the “manosphere,” a prevalent internet culture that, in my opinion, developed because of the absence of other spaces for boys and men to explore masculinity. Rather than promote positive exploration of male gender roles, the manosphere rationalizes a radical transformation of these issues.

Most creators in this space take the stance that society, not men, are the issue and that society is at fault for leaving men behind. The rhetoric is a convincing mix of degrees of truth coupled with a rage at a world that has failed them, as well as an overzealous acceptance of even the most negative traits associated with masculinity.

I had a very liberal upbringing in Hyde Park. While manosphere content filled my online spaces, I had other positive influences. I’m lucky to have been raised by a strong working mother and a father who wasn’t shy about having hard conversations with me about how to think about yourself as a man in the 21st century.

Because of this I’ve had a relatively healthy relationship to my gender identity. I’m a person who has always been comfortable not fitting in with the majority of my peers, so I didn’t ever feel pressured to do typically masculine things. Sports didn’t particularly interest me. I’ve always loved video games, which has generally been an activity for boys. Essentially, I took the parts of societal norms that I liked and left the rest.

Despite this, I think that my friends and I have been influenced by these radical ideas. The incel philosophy of looking at the dating economy as a zero-sum game where in order to be desirable you have to strive for financial and physical gain has played a role in that way that I think about relationships. This ties into what I’ll broadly call hustle culture, which pushes the idea that to be a man is to be a worker. On its face this isn’t a bad thing. There’s nothing wrong with a man who wants to push himself to improve in any number of fields, but when it becomes self-destructive, problems arise.

I personally have also struggled with emotional vulnerability, particularly with other men. Emotional reservation is something that is generally encouraged as a man — a broader part of not showing weakness of any kind. I’ve internalized this behavior without consciously choosing to. It’s something I really need to work on, and the solution can only come from me.

Boys and young men need a new definition of what it means to be a man that allows positive expression of gender identity while not invalidating or dominating the identities of others. This has to be a shared societal project. Men have to recognize negative behaviors they’re involved in while not wholly rejecting their gender identity. Finding this balance is difficult, and will largely be an individual process, but it has the potential to make men’s lives, and the lives of those around them so much better.

Societal deficits help drive manosphere

Society encourages men and young boys to conceal their emotions and to channel their feelings into actions or aggression, studies show. Some experts say this may help explain why they tend to be perceived as less emotional.

“I think the message for young boys is often ‘figure it out, come up with an action plan and implement that, or suck it up and go play sports,’” said Dr. Elizabeth Kieff, a psychiatrist in private practice who is also a U-High parent.

Dr. Kieff believes that sometimes, this messaging results in boys viewing their emotions as an issue rather than a feeling, and continue to later in life.

“They’re viewing a negative emotion as a problem that needs to be solved,” Dr. Kieff said, “and so they’re immediately making it an intellectual question, rather than an emotional piece of information.”

Dr. Kieff believes that this approach to expressing and dealing with emotions is unhealthy and unproductive for boys and men.

“There are some emotions — in fact, a lot of emotions — that aren’t problems to solve,” she said. “The death of a parent, a fight with a spouse. Sometimes it’s about being able to listen or being able to express your own vulnerability.”

Studies show there is no biological basis to suggest that women are more emotional than men. However, historically, the culture both in the United States and elsewhere has propelled gender norms in which men are expected to display fewer emotions and women are expected to show more.

“We still glorify strength and power and decisiveness and problem solving and intellect,” Dr. Kieff said, “and not men who are able to cry or say, ‘This was moving to me’ or shine and show strengths in other ways.”

None of this, experts say, is an explanation or justification for men who resort to violence or participate in highly aggressive groups. Still, for many men with no involvement in extremist movements, the pressures are significant.

“I think that that leaves a lot of men who might not be physically super strong or who might feel things more deeply feeling like there’s not a lot of outlets, ” Dr. Kieff said, “or maybe even language for them to use around that.”

Indeed, Dr. Kieff said, there is a growing understanding of the failings of cultural expectations for men when it comes to expressing emotions.

“I think there’s good hope today, too, because I think part of what has shifted is there’s been a recognition of toxic masculinity,” Dr. Kieff said. She added, “All that kind of stuff is really exciting. And I do think that there’s some change in your generation that would point to that.”

Who’s who

Manosphere influencers thrive in social media spaces, propelled by algorithms on TikTok, YouTube and Instagram. Audiences of young boys and men are drawn in by videos that claim to explain how to gain confidence, how to get muscles or how to get girls’ attention, but quickly, viewers are funneled toward more extreme and damaging topics. These are three of the countless creators that make up the online manosphere.

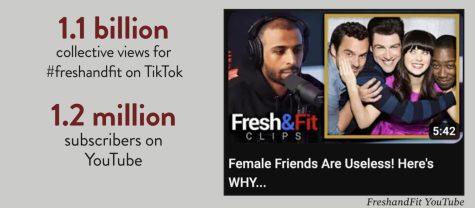

(Walter Weekes and Myron Gaines):

Walter Weekes and Myron Gaines are the co-hosts of The Fresh and Fit podcast. On the podcast, the hosts have spread disinformation about rape and sexual assault, sent their audience to harass women online, disparaged Black women and allegedly pressured guests for sex. The podcast draws in viewers with relatively innocuous fitness content and edited clips on FreshandFit YouTube TikTok. Popular clips show the hosts “owning” women they invite on the podcast, but these clips are misleading: female guests have their phones taken from them before recording and are given shots until they’re extremely drunk. Usually, the unprepared and inebriated women struggle to coherently answer gotcha-style questions, seeming to vindicate the hosts’ sexist views.

Sneako (Nico Kenn De Ballinthazy):

Sneako’s social media career shows a tragic example of how young boys can be radicalized by manosphere content. When he started YouTube in 2013, Sneako was barely a teenager. He became popular for his unique editing style and his often nuanced and self-aware commentary. However, in the past few years, Sneako’s content pivoted as he began to idolize creators like Andrew Tate. Sneako’s more controversial videos were more successful, further driving the creator

to make problematic claims. In 2023, Sneako’s content is unrecognizable. He’s come under fire for acting out sexual assault against a different creator who criticized him, platforming neo-Nazis who promote “scientific racism” and arguing against gender equality.

JustPearlyThings (Pearl Davis):

Pearl Davis is one of the few female manosphere creators. She lends apparent credibility to other creators’ misogynistic taking points by voicing her agreement as a woman. Davis, while portraying herself as a “high-value female,” often ridicules other women on her podcast called “The Pregame.” She gained popularity through associating with other popular creators, appearing on both of the above channels as well as Andrew Tate’s. On her own channel, Davis focuses her content on “exposing modern women,” negatively portraying single mothers, feminists and women who express self-confidence. Davis often claims that traditional gender roles are necessary and that modern women breaking away from those roles is ruining society.

Dog whistles

The videos, forums and podcasts that comprise the manosphere use a unique vernacular to describe specific concepts.

Many of the terms have been adopted from science or pop culture, but crucially, the original meanings are warped and widely misrepresented. Hopefully, understanding the vocabulary shared online can allow people in the real world to recognize problematic concepts and push back on misconceptions.

Hypergamy

Hypergamy is the concept of “mating upwards,” a biological phenomenon in some species of animals, incorrectly applied to women. Manosphere content often uses the concept of hypergamy to claim that all women try to cheat, all women use men for their money or status, and that women can’t build genuine friendships with men.

The red pill

The symbol of the red pill comes from “The Matrix” movies, but the term has been adopted online to indicate a particular word view. Someone who has “taken the red pill,” is someone who is aware of the “truth” about female nature and society’s unspoken hierarchy of value. Community members believe that being “red pilled” allows men to manipulate the invisible system to their benefit.

The black pill

The black pill is an offshoot of red pill philosophy, but someone who is “black pilled” believes that the truth they are able to see is inescapable. The black pill argues that “low-value males” are unable to socially succeed and will never be in a relationship. This is a particularly dangerous belief, creating communities that foster depression and sometimes violent behavior.

Gynocentrism

Gynocentrism is an incorrectly adopted term used by the manosphere to articulate the belief that society is controlled by women to the detriment of most men. Gynocentrisum is often used to argue that the wage gap isn’t real, that rape culture isn’t real, and that women weaponize complaints about structural sexism to harm men. In the manosphere, gynocentrism is often described as unnatural and as the source of most social issues.