On a quiet stretch of the West Woodlawn neighborhood, less than two miles from the Laboratory Schools, two-flat buildings line South St. Lawrence Avenue, one after the next. But one brick home stands out. Lush foliage fills its lawn. Tall red scaffolding stands beside it. Most of all, giant, haunting photographs loom from the windows.

This is the boyhood home of Emmett Till.

Organizers are transforming this residence into a house museum in memory of Emmett and his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley. They aim to open it to the public in 2025.

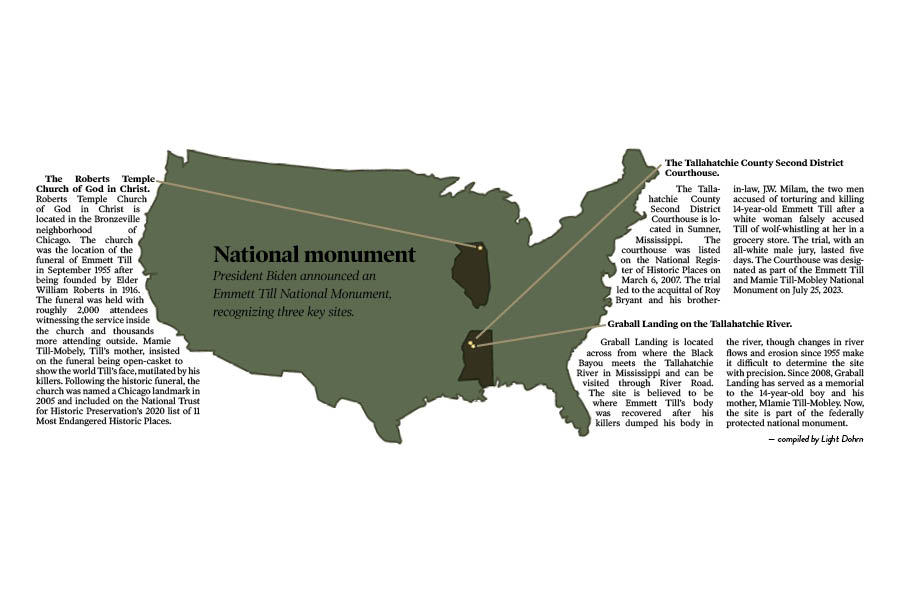

The creation of the house museum comes at a time of renewed attention to Till’s life and legacy: President Joe Biden this summer established a national monument honoring Till and his mother at three locations in Chicago and Mississippi.

“We are charting a future for a sustainable community and at the same time demonstrating how the tragedy of Emmett Till’s murder and death can be transformed from trauma and grief to triumph,” said Nuri Madina, Sustainable Square Mile director at Blacks in Green, a group that focuses on renewing neighborhoods in sustainable ways amid climate change and is leading efforts to create the Till house museum.

In 1955, when Emmett Till was 14 and on a trip to visit family in Mississippi, he went into a grocery store. The white woman behind the counter accused him of whistling at her, and he was later kidnapped, beaten and killed by white men.

Back in Chicago, his mother, Ms. Till-Mobley, insisted on having an open-casket funeral, forcing the world to see Till’s mutilated body.

“Let the world see what I’ve seen,” she remembered telling the funeral director in her memoir, “Death of Innocence.” Tens of thousands of people attended the visitation and funeral services on Chicago’s South Side.

The home, where Emmett Till and his mother had lived on the second floor of the two-flat at 6427 S. St. Lawrence Ave. since the early 1950s, has switched between ownership in the decades since his death, officials said. Plans to renovate the building and turn it into a house museum where visitors can recall his legacy are now underway, in part with help from a $150,000 grant from a historic preservation fund and as city officials deemed the site a Chicago landmark.

Over the passing years, some worried that the home’s history might be forgotten, or that it might simply become part of efforts to redevelop the neighborhood.

“The real value and history of the building was largely ignored,” Mr. Madina said, adding later, “we believe that that legacy should not be lost to the mere development of a property.”

Working with Blacks in Green, Germane Barnes, an associate professor of architecture at the University of Miami, created an art installation outside the Till-Mobley home this summer that he called “Be Careful I Always Am.”

Mr. Barnes said that the work, which included yellow and red vertical segments, was meant to connect Emmett Till’s experience with that of Black teenagers today.

“The history of Emmett Till is so powerful and many young Black men from Chicago resonate with his story,” Mr. Barnes said.

Mr. Barnes, who himself grew up in Chicago, said that he hoped the museum could be a place where young Chicagoans could “learn more about what is happening in the community and educate themselves on the other important but unheralded figures in Chicago’s history.”

To the organizers of the project, the house helps preserve the memory not only of Emmett Till’s tragic end but also of the journey to Chicago that his family had taken from the South in the first place, as so many other families had experienced during the Great Migration.

Still, Emmett’s Till’s final days must loom large in the house museum.

“We hope visitors will understand the innocence of a 14-year-old who assured his mother that he would be careful, without realizing the perils of the South at that time, and how the slightest misstep could endanger his life,” Mr. Madina said. “We have to depict the horror he experienced, and the path that his mother Mamie took to transition her grief into forgiveness.”

Timeline

1955: Emmett Till, travels from his home in Chicago to see southern relatives when he is kidnapped and brutally killed after going to a white-owned grocery store in Money, Mississippi.

2004: The FBI reopens an investigation after two men were acquitted by an all-white jury years earlier. By 2006, officials said the statute of limitations on civil rights violations had expired.

2007: Officials in Tallahatchie County, where the killing took place, issued a public apology for the first time to Emmett Till’s family. By then, his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, had died.

2017: The Department of Justice reopens the investigation after an author says the grocery store proprietor admitted her accusations were false. The new probe ends without charges.

2022: President Biden signs into law the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, making lynching, an atrocity carried out against thousands of Black Americans, a federal hate crime.