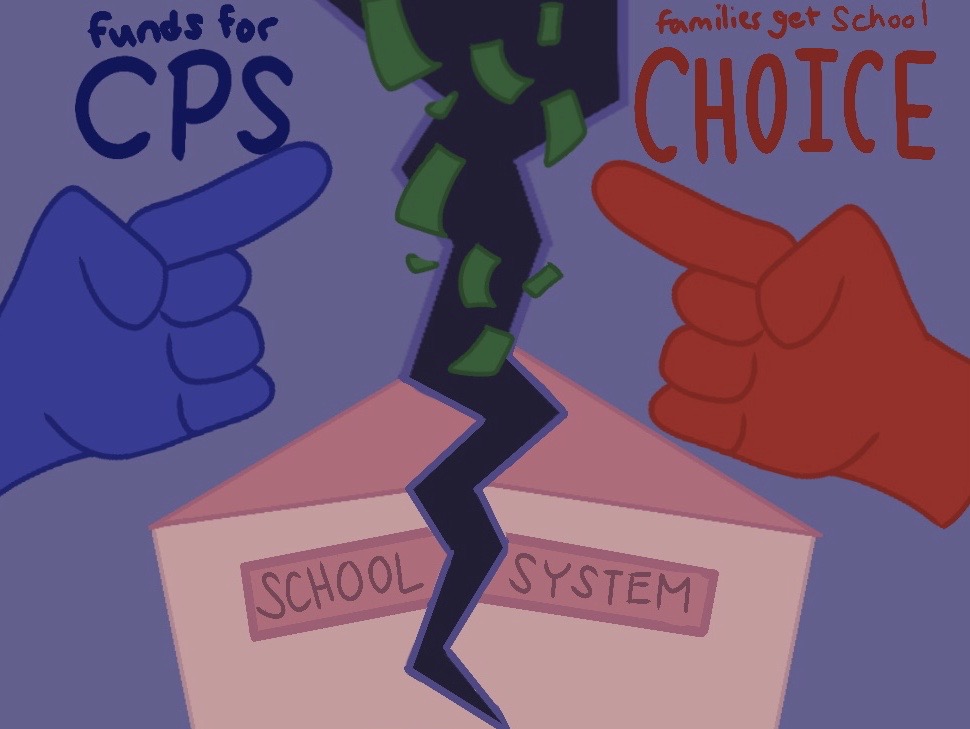

After Illinois lawmakers decided not to renew the Invest in Kids Scholarship Tax Credit Program at the Nov. 9 fall veto session, reactions were split. While some commend Invest in Kids for giving Illinois low-income families school choice, others argue the program diverts funds that could be otherwise channeled to Chicago Public Schools.

Enacted as a pilot program in 2017, Invest in Kids incentivized private individuals and businesses to donate to Scholarship Granting Organizations through a 75% income tax credit, giving students from low-income families the opportunity to attend private schools. More than 9,600 students currently receive scholarships and will continue to until the end of the 2023-24 school year, despite the program’s Dec. 31 expiration date.

The news is a significant loss for the Illinois Policy Institute, a conservative-leaning nonprofit that seeks to watch government action and serve as a voice for taxpayers.

“We talked to a lot of families who are receiving help from the program and may need to quit a job in order to homeschool their children,” Mailee Smith, Illinois Policy’s senior director of labor policy and staff attorney, said in an interview with the Midway. “Many of them are left not knowing what the next step is going to be. Come the end of this school year, thousands of families are left without viable options.”

On the other hand, Dan Montgomery, the Illinois Federation of Teachers president, released a statement on Nov. 9 applauding the end of the controversial program.

“Today, Illinois lawmakers chose to put our public schools first and end the state program that subsidized private, mostly religious schools, many of which have discriminatory policies,” the statement read.

Halle Quezada, a member of the Chicago Teachers Union and CPS teacher at the Mosaic School of Fine Arts, said she was pleased to hear about the program’s fate. She said CPS is in desperate need of funding.

“Our after-school programming has been in decline,” Ms. Quezada said. “Our sports have been more and more complicated to continue. Looking at my direct neighborhood, we are lucky if we can raise $2,000 in a year from parent fundraising.”

Ms. Quezada said she talked to her local representatives and encouraged them to find a different way to support the kids receiving help from Invest in Kids.

“If it’s that important to people that they opt out of our public schools, then I feel like it is very reasonable that they fund that through their own needs instead of money that could be channeled to public schools,” Ms. Quezada said. “Maybe the schools that are welcoming these children could shoulder the responsibility to help them afford it — private schools with private money.”

Ms. Smith argues the program does not detract from Chicago Public Schools. She said the money was never meant to go to public schools.

“By removing the tax credit, it’s not like the money is now going into the public school system,” Ms. Smith said. “More likely than not, it’s not going to be donated to a program that gives scholarships.”

Ms. Smith said lawmakers are not listening to the people. She’s referring to the results of a poll conducted by Impact Research, a public opinion research and consulting firm, and other research showing that most Illinois voters supported the program.

“If lawmakers listened to their constituents, this program, or one like this, would go on because voters actually support this program,” Ms. Smith said. “The data shows that there is vast support for the Invest in Kids program or school choice.”

U-High students are also considering what the end of the program means. Junior Raza Zaidi said he is unsure if he agrees with the decision.

“It is giving these kids the option in the first place to go to schools that may have a more rigorous curriculum, or that may have resources,” Raza said. “The drawbacks, however, could be that offering income tax credit takes money away from funds that would be going to public schools, which help the vast majority of people.”

Ninth grader Saanika Dutta said the program is beneficial and does not inherently take away from CPS but that more effort should be made to fix the larger problem.

“If you fixed the underfunded public schools problem, you wouldn’t even need programs like these to exist,” Saanika said. “It is a great program, but there should be other efforts made for public school funding — for more opportunities to be given to public school students.”

While some people say the program’s termination is a step in the right direction, others hope Illinois lawmakers will reconsider the program or another like it in the spring legislative session.