On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Over the months that followed, as the virus spread, it affected nearly every aspect of people’s daily lives. Now, four years later, its negative effects on health are still apparent through a subsequent iteration of the condition: long COVID.

According to 2022-2023 findings by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than three-quarters of Americans 16 and older have been infected with COVID-19 at least once. Of nonhospitalized adults who had an acute infection, 7.5% to 41% were estimated to contract long COVID, the CDC stated in an August 2023 report.

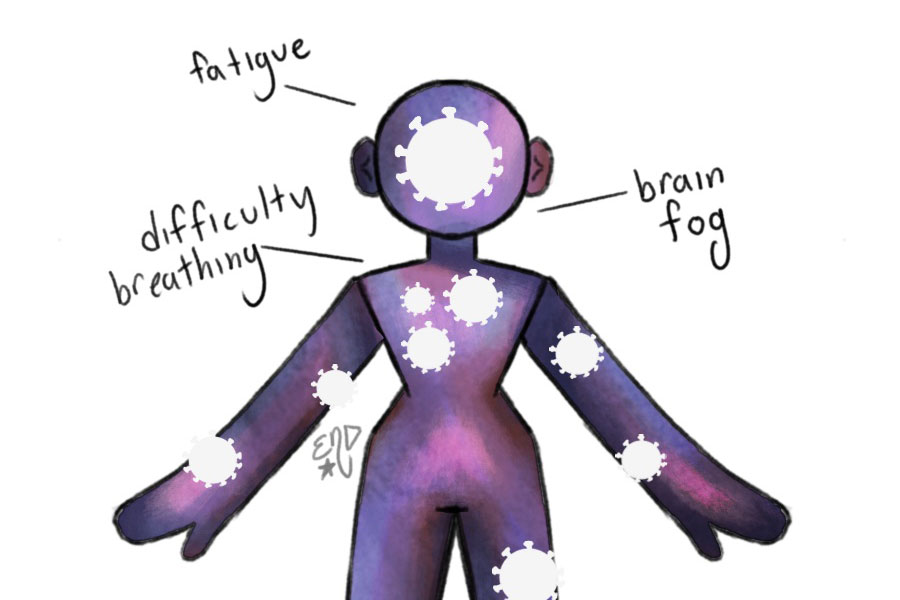

Long COVID is defined by the WHO as the continuation or development of new symptoms three months after the initial infection, with symptoms lasting for at least two months with no other explanation. This definition is just one way to identify the condition. Many doctors believe the definition of long COVID is much more broad.

“Everyone is going to have slightly different definitions of long COVID when it comes to research purposes,” David Zhang, physician in pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Chicago, said. “From a very general perspective, long COVID to me is defined as not returning to your baseline state of health after developing an acute COVID infection.”

Despite the broadness in definition, symptoms of the condition individuals experience are similar to those of regular COVID-19 infections, including fevers, coughing, runny noses, congestion and headaches. Despite this, some psychiatric-oriented effects, especially fatigue and brain fog, are particularly damaging in extreme adolescent long COVID cases.

“One of the things that we’ve seen more often in adolescents and teenagers is an exacerbation of ongoing mental health conditions,” Simon Parzen-Johnson, assistant professor of pediatrics at UChicago Medicine, said. “There’s definitely a signal that suggests that there’s increased diagnoses of psychiatric conditions and neuropsychiatric conditions after having had COVID.”

While long COVID is more common in adults, findings show it is still prevalent among adolescents. About 18 million adults are estimated to have symptoms at least six months after their acute infection and about 5.8 million children, according to a February 2024 review from the Journal of Pediatrics.

“The definition is so variable that each study that pulls people in is going to be a little bit different. But the point is that, regardless of whether they have the strictest definition or the vaguest definition, that’s still a significant number of people,” Dr. Parzen-Johnson said.

As in regular COVID-19 cases, symptoms and severity of long COVID in adolescents varies greatly person to person. In severe cases, the condition can significantly alter a person’s daily function.

“I’ve seen kids who are high performing, have good grades at school, doing well in their activities, and then they get COVID and then there’s actually a significant decline in their function,” Dr. Zhang said.

At Lab, no formal complaints of long COVID have been reported. Still, some students have experienced enduring COVID-19 effects such as fatigue.

“Thankfully, long COVID has not been a topic of concern or discussion for us nurses here at Lab within our community that has been affected with COVID,” U-High nurse Mary Toledo-Treviño, said. “I think for our high schoolers, the biggest thing would probably be the chronic fatigue that would be most noted in patients that are dealing with long COVID symptoms.”

If a student is feeling persistent symptoms of COVID-19,measures can be taken at school to mitigate its impact.

“Lab is a very academically rigorous environment, and so a lot of our students really get worried about falling behind missing classes, falling behind on schoolwork,” Ms. Toledo-Treviño said. “Studies have shown that stress can delay healing, so what we try to do in our part is try to take some of that stress off, remind the student and the families that they’re going to be supported.”