It is a reality unto itself, a three-story testament, simultaneously recording a moment in history and reimagining it. 1960s and ’70s-style furniture has been carefully curated throughout, curved, pale pink and green sofas filling rooms. The furniture, the art and aspects of the layout come straight from the Johnson Publishing Company’s former headquarters and founder John Johnson’s personal collection.

The intent is not imitational but tributary. “Theaster Gates: When Clouds Roll Away,” an exhibition by artist and University of Chicago professor Theaster Gates, displays archives and restored furniture from the former headquarters of the Johnson Publishing Company empire. The exhibit, presented by the Rebuild Foundation, appears at the Stony Island Arts Bank.

Founded by John Johnson in 1942 and headquartered in Chicago, the Johnson Publishing Company dominated the market for media targeted to the Black community through the rest of the 20th century.

Gelasia Croom, the Rebuild Foundation’s director of communications, said she believes the works of Mr. Johnson and of Mr. Gates bears a similar commitment to the preservation of Black culture.

“This building that we’re in is an example of Mr. Gates’ willingness and desire to preserve Black culture,” Ms. Croom said. “If you connect that and you look at what John Johnson himself was doing, that was the same thing.”

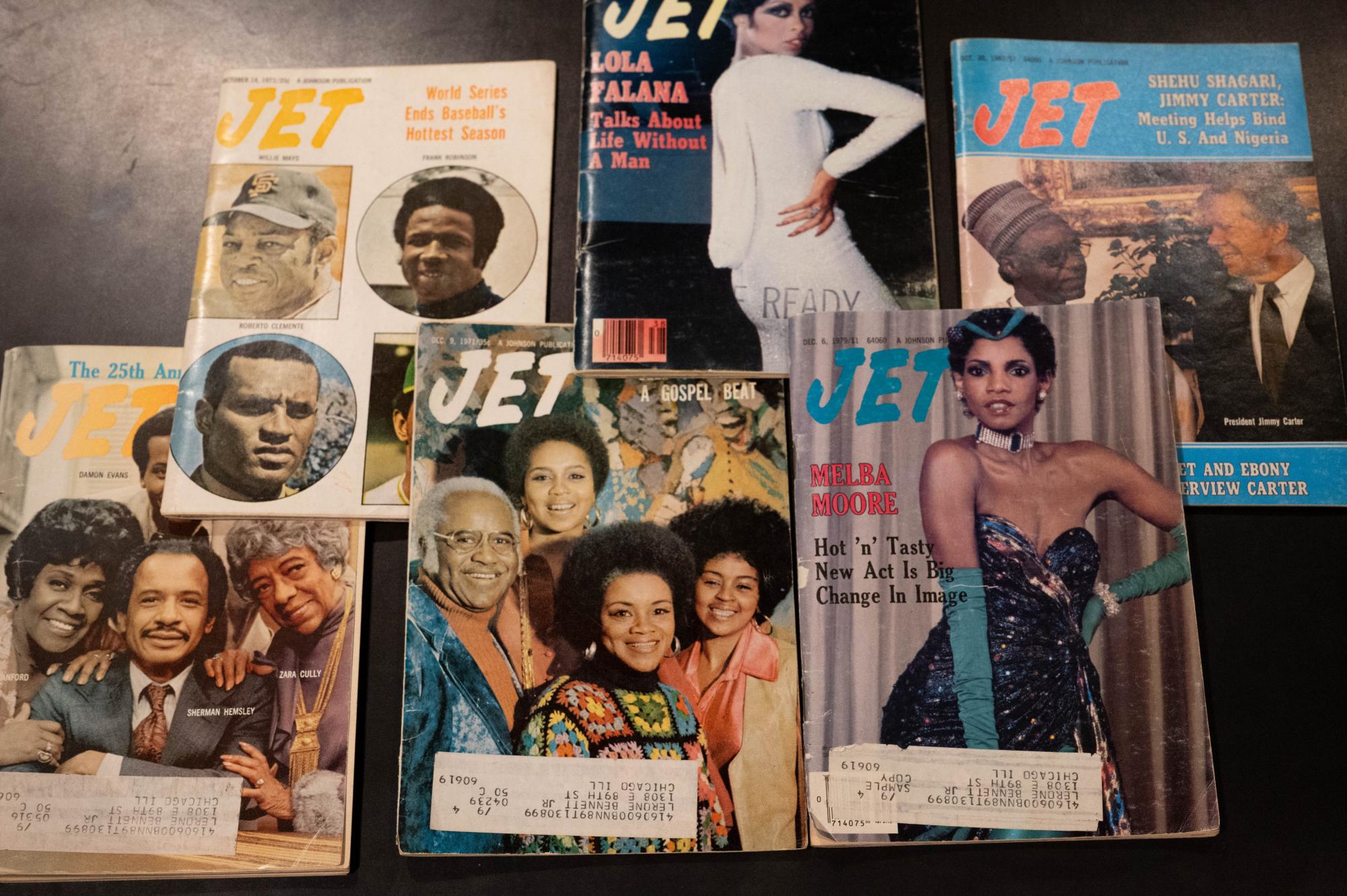

Mr. Johnson dedicated himself to depicting Black life in his publications, Ebony and Jet. These were monthly and weekly sister magazines that strove to combat racist rhetoric by illustrating the complexities of Black existence in America.

Ms. Croom said, “Ebony was really the flagship publication that allowed the opportunity for Black Americans to see themselves in so many different ways, as professionals, as part of movements, as part of the fabric of American culture.”

The iconic magazines, which began their publication in the 1940s and ’50s, continued until the 2010s, when the company sold their headquarters and both publications. Johnson Publishing Company continued under the leadership of CEO Linda Johnson Rice, Mr. Johnson’s daughter and a U-High alumna.

Mr. Gates has been in possession of the Johnson Publishing archives and furniture he acquired as part of his work with the Rebuild Foundation for around a decade. According to Ms. Croom, most of the furniture has only recently been restored for display at the Stony Island Arts Bank.

The former bank is home to the archives and collections of the Rebuild Foundation, an organization founded by Mr. Gates, which serves as a platform for “art, cultural development and neighborhood transformation,” according to its website.

Stony Island Arts Bank was originally a savings and loan, until its closure in the 1980s. The building lay abandoned until 2010, when Mr. Gates purchased it for $1. It reopened in October 2015.

Its current exhibition, “When Clouds Roll Away,” spans all three floors of the building. The first floor is home to the only interactive part of the exhibit, which is called “Facsimile Cabinet of Women’s Origin Stories.” Originally displayed in Switzerland as part of a different exhibition by Mr. Gates, this work allows visitors access to facsimiles of photos from Johnson Publishing Company’s publications. The photos depict Black women, ordinary and famous alike. Visitors can arrange them for display, picking and choosing the narrative they want to curate.

The exhibition comes together as the para-fictional headquarters of the Black Image Corporation, a fictional contemporary Black publishing company. This echoes Mr. Gates’s earlier work. According to a recent New York Times profile on Mr. Gates, his first major exhibition was para-fictional, a genre that explores the overlap between fact and fiction. In the exhibit he displayed works by an artist whose existence and life story he had invented. It wasn’t until later that he admitted to the work being his own.

Unlike his first exhibition, “When Clouds Roll Away” doesn’t attempt to trick its audience, but rather lets them in on the secret. The viewer is simultaneously aware of the fictitious and real aspects of the display.

As one emerges from the stairway into the first room on the second floor, a quote from Mr. Gates defines the intent of the exhibit to “honor artists as the best messengers for the reactivation of old stories.” This quote deftly summarizes the strength of this exhibit, capturing the importance of preservation.

As she walks around the museum, Ms. Croom talks about her family’s home. It was filled with stacks of Ebony and Jet that would teeter in unstable columns throughout the house. Her mother refused to throw away any of the issues, keeping them as proof that Black life was worth recording. Now, old issues of Ebony and Jet spread across a dark-stained wooden table in the library of the Stony Island Arts Bank. Volumes from John Johnson’s personal collection inhabit floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. Theaster Gates is safeguarding the tradition of preservation. In fact, he’s turning it into an art form.