Ace Zhang

Not straight, not seen

March 25, 2019

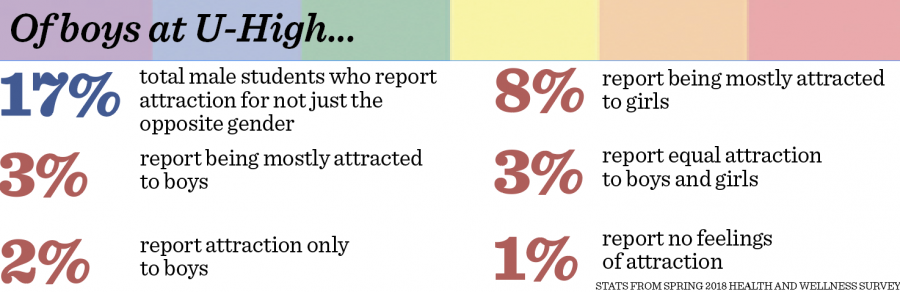

According to the wellness survey administered last spring, about 17 percent of male students at U-High reported romantic attraction for more than just members of the opposite gender or no sexual or romantic feelings. Yet only a small number feel comfortable being out to the wider community.

Fearing stereotypes, boys don’t express sexuality

“I’m not trying to deny it or hide. It’s just a part of me, but you don’t have to know,” a senior boy said, referring to his sexual orientation. “If someone came up and just asked me I’d be like, ‘Yeah, sure, what about it?’”

The senior, “David,” who asked that his real name not be published, is one of dozens of boys at U-High who don’t identify as heterosexual but don’t feel a need to publicize it. Some have concerns that their sexual orientation would overshadow other aspects of their personality.

That shouldn’t be the case, according to Alexis Tyndall, a senior who identifies as bisexual. She said that the U-High community needs to accept that sexuality is fluid, and that acceptance is needed especially for boys.

“I know a lot of people who come out after they go to Lab — also because Lab is such a small community that once something is said and done, everyone knows and that’s it, and you can’t really go back or explain yourself,” Alexis said.

David said he’s attracted to men and women, but doesn’t want that to be his defining characteristic.

“It’s just something about me,” David said. “When I first meet people, it’s not what they immediately know about me. Once they form an opinion of me and once they know who I am, then they find out.”

Other male students have questioned their orientation for a long time. John Freeman, a junior, said he now identifies as gay and is just starting to share his sexual orientation with the wider community. He said he didn’t want to be put in a box.

“I’m a male ballet dancer,” John said, “and there’s definitely a connection that some people associate with ballet dancers and being gay, and that association actually made it harder for me to accept [my sexual orientation].”

He said he initially identified as bisexual, but didn’t share his orientation with anyone until he realized he was gay.

“When you’re in the closet, it feels like every little movement, every little word you say could say something — just as much as if you’re talking to someone you like and you’re worrying about every movement, like what does that say about me,” John said.

It was validating, freeing, to come out to his inner circle, including friends and parents, John said, but along with David, John thinks the idea of coming out to the rest of his peers seems ridiculous.

“I don’t want to go around the whole school telling everyone because that’s weird. It’s not like it’s something that’s super important. It’s just an aspect of identity,” he said. “Like, I wouldn’t go around the whole school saying, ‘I’m white, hi, nice to meet you.’ But I don’t want to hide either.”

David said he doesn’t want people’s stereotypes to color how they view him, so people aside from his close friends don’t know his sexual orientation. Plus, he believes the process of coming out just seems like too much trouble. It’s high risk with a low reward: potential embarrassment, a storm of preconceived notions, an assault on his personality — and the people he’s close with already know, so why does anyone else need to?

John said part of the reason he doesn’t express his sexuality in a more public way is because it seems like too much effort for him, but he praised his peers who are more visible.

“I have a lot of respect for that, but it’s just not how I choose to show my sexuality. I applaud them for being so open,” John said. “I want to be open, just maybe not to that extent.”

But David says the guys who are out often let their sexual orientation define them. He finds it annoying, cringe-worthy, fake. If someone isn’t straight, it seems to David that it’s difficult to successfully integrate sexuality into identity — though maybe less so for girls.

“With girls, no one really cares. With guys, you see them differently when they come out, but with girls, I don’t think it’s the same,” David said. “I don’t want to say they have it easier, but it’s more normal. I don’t know why. I wonder that sometimes. I think it’s just less common for guys.”

Alexis said she didn’t come out with a “grand gesture.”

“I had friends that were going through the same thing, so we all just kind of bonded over that,” she said. “I’d say that my larger friend group in my grade kind of fed off of that energy, and therefore it was kind of like, ‘Oh, whatever,’ because there was a whole group of people who were all not straight.”

She said she will only share if it’s relevant.

“I don’t really just tell people,” Alexis said. “If it doesn’t come up, I feel like there’s not really a need, but if it comes up in conversation or I have something to add to a conversation, I don’t really mind telling people.”

Changing the climate

Title IX Coordinator Betsy Noel said the school’s climate needs to change. While students are “well-intentioned toward inclusion,” there’s still a lot of work to be done.

Along with students at U-High still making “that’s gay” jokes, Ms. Noel said, “There is a long history of our, and the country and U.S. society generally, curriculum and practices being heteronormative, and that can cause students who do not identify that way to feel isolated in more subtle ways that can still have a big impact on their wellbeing.”

Some people around the school are doing good work, according to Ms. Noel, praising the members of Spectrum, some faculty and Priyanka Rupani, Lab’s director of diversity, equity and inclusion. But Ms. Noel said she thinks the community needs to work on heteronormative “language habits.” Students also need to work to change the culture.

“There isn’t a conversation about or space for supporting students who are more diversely interested than just exclusively heterosexual or gay, and helping them feel safe in being open about and understanding those feelings,” Ms. Noel said. “It is also critical that we start these efforts around inclusivity well before high school, as demonstrated by the survey data that shows the younger Lab students are actually more diverse in their attraction than the high schoolers.”

Deb Foote, a world language teacher who recently became adviser to Spectrum, said Lab could improve through more visibility and opportunities for LGBTQ+ students to explore and embrace their individual and collective identity.

“I would like to see more visible recognition and energy devoted to addressing issues related to the LGBTQ+ community and opportunities for students,” she said, adding that if the community made awareness and visibility priorities, then the administration would, too. “It has to start with students, though.”

‘Out’ students feel Lab accepts them

Compared to past experiences, Lab provides comfort.

The process of accepting his sexual orientation was gradual, but once he knew, senior Ryan Lee wanted to be out immediately.

“It was gradual to accept the fact that. ‘Oh, I’m gay’ and I came to terms with the fact like, this is a part of my own identity,” Ryan said. “And then after that, it was kind of just sharp, like, now I can come out to everybody.”

Last spring’s health and wellness survey showed that about 17 percent of boys at U-High identified interest other than only heterosexual. However, a much smaller number of male students has shared this identity widely within the U-High community. But those male students who are out find Lab to be an accepting community, partly because they believe their peers see them as whole people — their sexual orientation is just one aspect of their identity. They also say they did not experience significant negative repercussions for being out.

Ryan, who joined Lab in seventh grade, said during his freshman year, he saw many people come out and observed as they were accepted by the wider community.

“Part of it was, first seeing how much support there was when someone else came out. And then once I saw that — especially considering the stark difference with my past school — that helped me gain a lot of trust really fast,” Ryan said, referring to his previous suburban public middle school.

For Ryan, the process of coming out publicly was slow. Ryan explained that having a few people he could trust went a long way to helping him be comfortable.

“It’s always nice to find one or two people that you can really confide in,” Ryan said, “even if they aren’t your family, and come out to them and find a support group and then start building outwards from there.”

The process of coming out was different for senior Robert Coats, who had already come out when he joined U-High as a freshman.

“It was another process of coming out, but I didn’t want to go through high school pretending to be someone I wasn’t,” Robert said.

Robert said that the reason he sees Lab as such an accepting community is that he is not defined by his sexual orientation, but instead just as himself.

“I think Lab sees the whole person not just one individual part of your identity,” Robert said.

Both Ryan and Robert expressed that their experience in U-High has been better than experiences outside school.

“I feel very accepted here, especially compared to the school I went to before,” Ryan said.

Robert, a Boy Scout, felt uncomfortable with this aspect of his identity until the Boy Scouts of America allowed its members to be openly gay beginning in 2015. But, even then, he did not feel fully comfortable being in the organization.

“I definitely feel like outside of Lab is where is where I’ve had most of my experiences for people that are a little bit less comfortable with non-straight people,” Robert said.

Although their experiences coming out differed, both Ryan and Robert say that aspects of U-High help to make accepting community.

“I mean, having Spectrum really helped just to, like, have a place where I could talk about it and understand that I’m not the only one that was confused at first — and then everyone’s just very open about it,” Ryan said. “So it’s a lot easier to just be gay than I thought it would be.”

Non-Lab pride leaders discuss vibe in schools

Allyship, according to pride leaders at other Chicago-area high schools, means more than not being homophobic. Working with administrators, they hope to promote understanding, not just tolerance.

Carter Wagner, Francis Parker School’s Pride Committee leader, said regular events prove effective when educating the community. The school holds three assemblies each year, as well as “ally meetings” where straight, cisgender students can learn about the experiences of their LGBTQ counterparts. Furthermore, Carter, a sophomore, said the presence of openly gay teachers at Parker positively contributes to an atmosphere of understanding and inclusivity.

Some students wish to be less public about their identities. Pride Committee holds bi-weekly safe spaces for queer or questioning students in which attendees often discuss the challenges of coming out.

“Because we create this safe space, many students still in the closet attend our meetings,” Carter said, explaining why these meetings are not open to straight students.

Through both public and private discussion, Carter said Parker’s community has come to understand the difference between tolerance and genuine support.

At Jones College Prep, students and faculty struggle with this distinction, according to Sara Decker, Pride Club board member.

“A lot of the student body believes that not being homophobic is enough,” Sara, a sophomore, said.

Sara said this lack of understanding, as well as limited education on LGBTQ history, often causes her school to downplay the issues faced by gay and transgender students. She said one incident involved conservative students at Jones claiming it was “more difficult to come out as conservative” than gay.

Julian Rivera, a transgender student at Munster High School in Indiana, echoed this criticism.

He said, “It’s a safe environment to come out but a trickier one to be respected and understood.”