Middle school teachers instill confidence

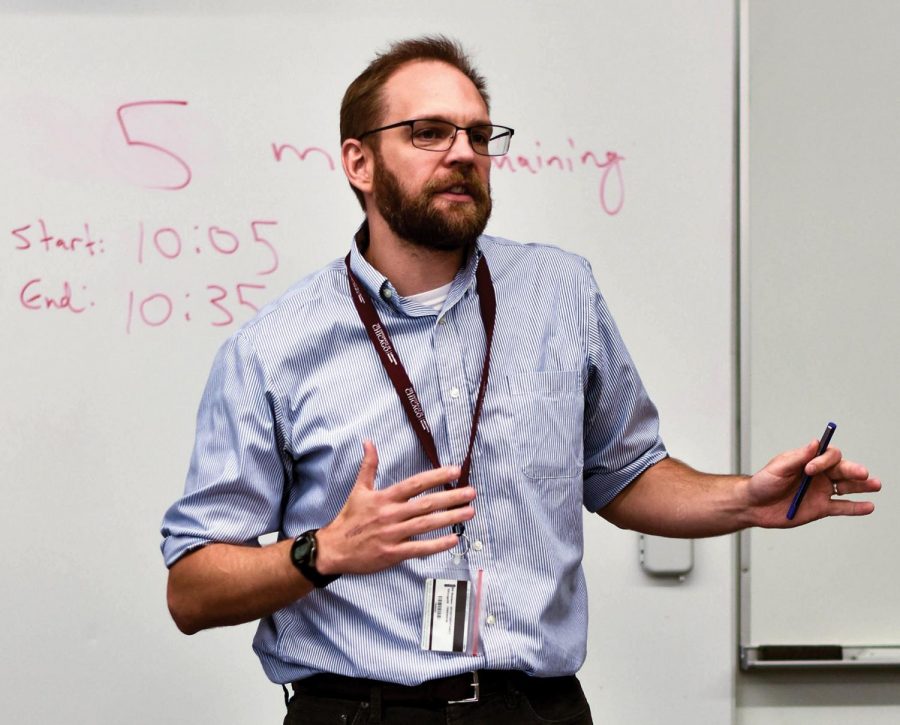

LIFE LESSONS. Standing in front of a white board, Humanities teacher Sam Nekrosius gives a demonstration to his seventh-period class. Combining English and History, The course encourages students to place their own identities in the context of American social justice.

October 9, 2019

There’s something special about the role of a teacher — it carries the authority of a parent, the guidance of a mentor, the regularity of a friend.

Humanities, a 90-minute class that combines both English and history, gives middle schoolers the opportunity to strengthen communication and explore topics such as identity and social justice. Even as they move through high school, certain students retain these early lessons and teacher relationships.

Hunter Heyman, a junior, still visits his seventh-grade humanities teacher, Sam Nekrosius. He and his friends still visit Mr. Nekrosius, he said, for a variety of reasons.

“We see him often, so that’s why I think he still has an influence,” Hunter said, reflecting on the significance of their relationship in middle school. “It seems counterintuitive because as you get older you’re more similar in age, but I think when you’re younger you can just talk to your teacher more, inside and outside of class.”

Mr. Nekrosius said he hopes he can facilitate interactions like this, starting right when students enter his class.

“I’ve learned to listen. I hope, and I think kids know, they can come and talk to me, and I won’t listen to them like they’re a child. Because they’re not,” Mr. Nekrosius said. “These are human beings that I know, and I’ve seen them struggle or suffer or succeed, and I’ve validated those struggles.”

But why do these classes have such a lasting impact on students? Elizabeth Lin, a junior, credits eighth-grade teacher Staci Garner for some of her current success, believing humanities has provided a foundation for later English and history classes.

Aside from the significance of the curriculum, Elizabeth said Ms. Garner’s teaching style has stuck with her.

“What I really liked about how she taught was that she held all her students to a higher standard than the other teachers,” Elizabeth said. ” So for me, it was always like, ‘Don’t disappoint me, because I believe in you.'”

This idea isn’t just Elizabeth’s perception Ms. Garner said that it’s part of her teaching philosophy to push her students and aim high.

“I’m kind of going to shoot as high as possible, and see who’s going to chase it. Kids won’t always reach it, they won’t always hit the mark, but that’s O.K. because it’s about expecting more of ourselves and where we could be,” she said. “When the bar is set low, it sends the message that not much is expected of you, and perhaps can be internalized to ‘you can’t really do that much.’”

Middle school humanities teachers can never be on autopilot — especially, Mr. Nekrosius said, because their work is so closely linked to how students develop.

“In a lot of ways, being a seventh grade humanities teacher overlaps my adviser role, in places where it’s almost seamless. Things that we talk about in advisory, identity, diversity, flirting versus hurting — anything that is developmentally appropriate — it all comes back again in the curriculum that I teach,” he said.

Ms. Garner shares this sentiment. She was sure she wanted to teach U.S. history, she said, because of the uniqueness of the American experience and the importance of relating as humans.

“No matter what your pursuit is in life, if we’re going to tackle enormous problems in the world, if you cannot relate to people and you cannot convince people that a problem is worth solving, then it doesn’t matter what technology you have in place,” she said. “If you can’t sell it, it’s not going anywhere. In order to do that, you have to make people care, and you have to reach them on a human level.”