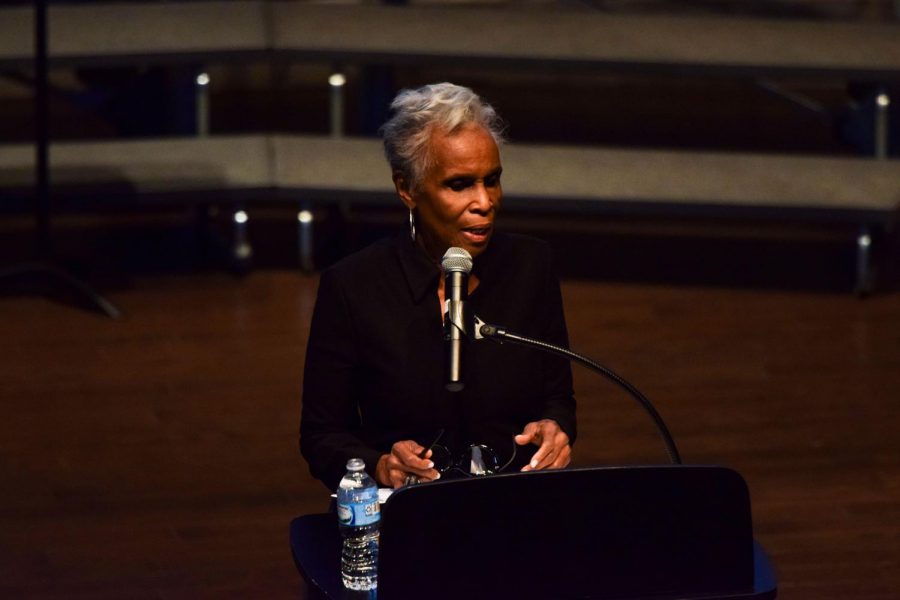

Pioneering journalist of color speaks about her career

“It’s urgent that those of us who have talent, journalists in particular, do take very seriously what it means to be truth-tellers,” said Dorothy Butler Gilliam, who was the featured speaker at the Martin Luther King assembly Jan. 16.

A trailblazer in her own right, Ms. Gilliam was the first black woman reporter for The Washington Post and one of the first black women to gain prominence in the journalism scene. Now, 17 years after her retirement, Ms. Gilliam spoke to U-High students about what it meant to make space for her identity in a world all-too-reluctant to give it to her. To Ms. Gilliam, the fight is still far from over.

“When you have that leader who is basically saying that, you know, one of the First Amendment rights, freedom of the press, is totally invalid, it’s a dangerous time,” Ms. Gilliam said.

Though she hasn’t worked as a journalist for almost two decades, her experience as a reporter showed her a lot about being a woman of color, and specifically a woman of color in the workplace.

Ms. Gilliam says that even if the truth is uncomfortable, a journalist, as a truth-teller, can only prepare for the shock that may come from that truth. During her time as a reporter, she saw female journalists fight to tell their truth.

“It wasn’t easy when we women sued The Post and the women [journalists] sued The New York Times all to have fair pay,” Ms. Gilliam said. Though the struggle for just pay was difficult and unpredictable, it was a truth that had to be exposed.

Beginning her career in journalism during the late ‘50s meant Ms. Gilliam would have a front row seat for the civil rights movement in America. As she covered stories such as integration of Little Rock Central High School, Ms. Gilliam also got to see what it was like to be a journalist of color who needed to travel around the country to do her work.

In Ms. Gilliam’s speech during the MLK assembly, she mentioned that journalism had opened new worlds for her. Specifically, when she wrote a society story, she saw the black middle class.

“I grew up among the working class in the segregated south… so it was just this new world for me to know that black people lived that way,” Ms. Gilliam said after recollecting what it was like to see that black people in the middle class might have enough money to afford fine china and silver.

When Ms. Gilliam was sent to cover a story at the University of Mississippi, The Post knew that she could not cover the whole story on her own due to the racial barriers she’d face. Her editor assigned a white man to the story as well because his identity would make it easier for him to complete the story.

“[The editor] said, ‘Think about it like you have green skin. Just don’t think about being a white person and don’t think about being a black person.’”

Ms. Gilliam’s identity has played a huge role in her career as a journalist, and because of it, she has learned how to be a better, more objective writer.

Ms. Gilliam said, “There’s a large percentage of white women who are in media power positons and some of them really want to effect change but still have a hard time because so often their bosses are male and they feel pressured to kowtow to them, which we have to stop.”