Teachers should consider cutting curriculum to increase learning

Students are overwhelmed with remote learning, and teachers must consider cutting curriculum.

December 7, 2020

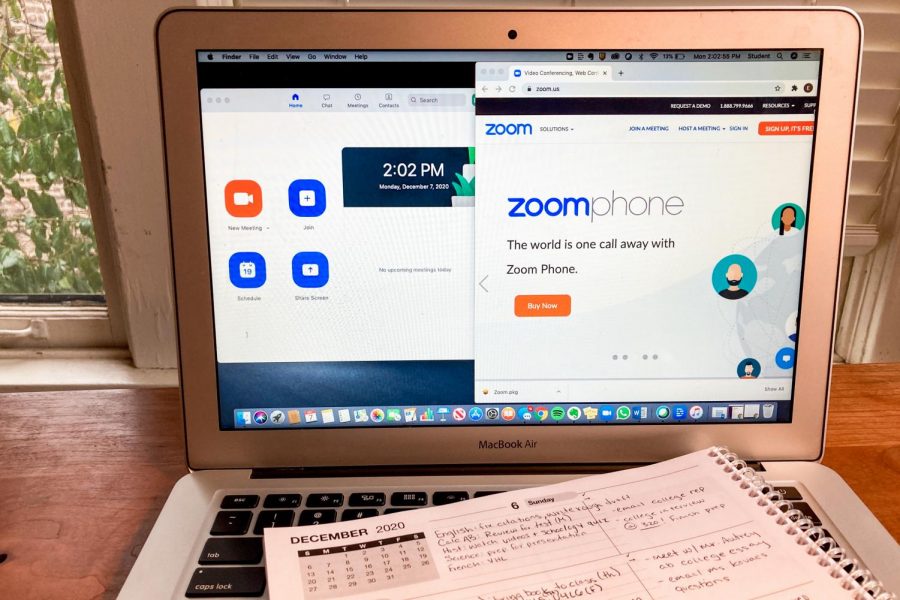

When students were told we would be starting the year on Zoom, none of us expected to be zooming through a demanding curriculum that leaves most of us exhausted and the rest of us behind.

Arriving at winter break, it’s time to seriously evaluate the effect that distance learning has on students. If the last 13 weeks have taught us anything, it’s that the distance learning curriculum across the board is too fast and too ambitious.

Heading into the school year, U-High transitioned to a block schedule, cutting each class’s time from three and a half hours a week down to just two. Lab sciences that previously met for four and a half hours were also reduced to two one-hour sessions.

In an effort to cover the same or a similar amount of material as previous years, many teachers have resorted to assigning more work between synchronous class periods. In our own classes, some assignments cover new material that is then not reviewed in class, leaving students responsible to teach themselves. These changes place significant stress on students and have led to complaints demanding a reduction in homework. But this issue is a double-edged sword, presenting challenges not only for students but also for teachers. Students cannot keep up with the vigorous work demand, but teachers also cannot significantly reduce homework load without sacrificing the curriculum.

If the challenges of distance learning are to truly be improved, classes need more than just a reduction in homework. Teachers need to be willing to adopt slower and less ambitious curriculums that accommodate for the changed atmosphere of school itself. Students are being forced to adapt to distance learning, and the curriculum needs to do the same.

Some teachers and departments may hesitate to make curriculum changes for fear that students will fall behind and have to catch up when school returns in person, especially in sequential classes that build on past knowledge. While these intentions are reasonable, teachers must accept that distance learning will, and already has, forced students to fall behind. Many of our peers have reported a struggle to focus and, with such fast-paced, rigorous schedules, are not absorbing information. When students have to learn new and unfamiliar material through homework or asynchronous work, the quality of their learning decreases because for many there is reduced incentive to complete quality work.

The shift to remote learning is not just the addition of a screen between ourselves and our fellow classmates, nor a simple reduction in class time — it is a completely different school experience. There is no point in trying to make an old curriculum fit in with a new school, especially one that is valuing quantity of work over quality. A slower and less-ambitious pace, where students are actually learning, should be adopted.

The inflexibility of curriculums could potentially set students, and the entire institution, up for failure when school finally resumes in person. Teachers are feeding into a system that favors the students that have the capacity to do well at distance learning. When we return, teachers and students will have to confront a learning gap that is slowly growing among students as distance learning continues.

It is beneficial to everyone if the curriculum is manageable for all students. Unrestricted by the AP curriculum, teachers have the ability to make these changes. Furthermore, these issues with distance learning are not limited to a single grade — they are happening across the whole school. Thus, it is logistically feasible and beneficial for departments to redistribute learning material along a four-year track.

This may seem like drastic demand, but without these changes teachers will eventually either have to re-teach material that students did not understand, or certain students will struggle academically without the appropriate guidance that they should be receiving.

Distance learning is temporary, so teachers and departments should be taking steps to ensure that their choices do not have long-term negative effects on students and their education. A student’s education should not be built around a curriculum, the curriculum should be built around the student.

Deb Foote • Jan 5, 2021 at 7:21 am

I am a Middle School teacher at Lab, and, therefore, so I cannot speak for High School teachers. I know I have been thinking a lot and working with my division and department colleagues to adjust curriculum and classroom expectations during remote learning. We are very concerned about balancing learning to help avoid student overload and burnout. Please know that at least some Lab teachers are making changes that attempt to maintain the integrity of the classroom and address students’ well-being.

Leeann Zouras • Dec 8, 2020 at 8:11 pm

Dear Editorial Board,

Thank you for your thoughtful opinion piece. It is overdue but much appreciated.

Everyone would benefit from a change of pace during these trying times, which for high schoolers may continue through the rest of the school year.

Lab still has time to tweak things, although I wouldn’t hold your collective breath.

Sincerely,

Leeann Zouras

Sunny Neater-DuBow • Dec 8, 2020 at 10:33 am

Dear Editorial Board,

I appreciate this piece so much and it is something I was grappling with going into this school year. Through the pandemic and all the ways it has been impacting us, I have come to understand that we can’t place our previous expectations of academic learning on this new reality. I have made a kind of peace with mining the content of my courses for what I believe to be most important to teach today, in the context of these zoom rooms.

I hear others’ concerns about “falling behind” and can’t help but ask myself, falling behind whom? Everyone in the world is experiencing this new reality, and as usual, we are among the most privileged, the most resourced, and the most supported in terms of access to learning and teaching. We will be among the most fine (if we survive this thing).

This year is different for the entire world, and we need to recalibrate our thinking on “where” we should be in terms of academic benchmarks, and also acknowledge that we are all spending huge amounts of time simply learning how to navigate this new reality with an inkling of grace, kindness, and good humor, and doing so alone for the most part, or more alone than we have ever previously been.

I appreciate the Editorial Board sharing its insights with us, and hope that we as educators can take your insights to heart as we continue to examine our curriculum, and our teaching and learning expectations.

Keep fighting the good fight.