Teachers work extra to handle new demands of distance learning

With extra tasks such as posting on Schoology and creating videos and slideshows, teachers find themselves with an increased amount of work.

December 10, 2020

It is well known that after students log off of Zoom for the night their work is just beginning as they attempt to sift through hours of homework. During distance learning, teachers have been forced into the same boat, many working late into the evening to prepare for the next day even after all synchronous classes have ended.

Despite reduced synchronous time with students, many teachers have found distance learning to entail more work than in-person learning with more repetitive tasks and working with technology. The result: they are exhausted.

“While technically we should have more time outside of actually talking to students, I think it gets shifted into a lot of other responsibilities,” science teacher Zachary Hund said. “I feel like I am much busier this year than I have had any of the other five years I’ve been at Lab.”

Much of that work accumulates in extra tasks teachers are doing to help their students.

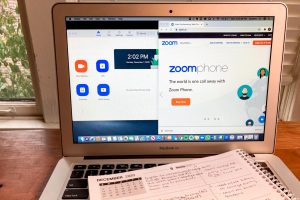

“Teachers in the math department like doing extra videos to reinforce material and it takes time to do that and upload them,” math teacher Shauna Anderson said. “We have decided in the classes I teach, we actually come up with class notes.”

English teacher Mark Krewatch has experienced a similar phenomenon teaching his English classes, and the increase in work has been severe.

“I don’t think I’ve had a non-seven-day week yet, and when I say a seven-day week, I mean, not like a couple hours on Saturday and a couple hours on Sunday,” Mr. Krewatch said. “I mean, five, six, seven, eight hours on Saturday and five, six, seven, eight, nine, 10 hours on Sunday.”

According to Mr. Krewatch, much of his time is spent planning for the synchronous and asynchronous activities for the week.

“Most of my nights are midnight and after, that’s just what it is,” Mr. Krewatch said. “You’re trying to plan and scaffold things for two hours of in-class time and then plan things that students can actually learn independently, outside of that time.”

Like Mr. Krewatch, history teacher Naadia Owens said distance learning has resulted in a surprising uptick in work and forced her to spend long periods in front of a screen.

“Reading on a computer is really hard for me,” Ms. Owens said, “so that definitely has felt like it’s increased my workload because I’m just trying to manage staying on top of my grading for students when I’m having trouble reading for long periods of time on the computer.”

According to Dr. Hund, the increased work demand is a challenge to keep up with.

“I feel like someone pushed me in the deep end here, and I am struggling to keep my head above the surface of the water,” Dr. Hund said. “I feel like there’s so much to worry about in terms of what’s necessary for my students right now that it’s hard to think two, three or four days ahead in terms of how can I start making things better or do things differently.”

Both Mr. Krewatch and Ms. Anderson find adapting lessons to an online format comes with a lot of added work.

“I’m not really huge on doing in-depth slideshows,” Mr. Krewatch said. “That’s not something that I normally do in class. I’d much rather use the whiteboard or just talk or hold up examples or show particular things that I can kind of click through. You can’t do that in [distance learning]. You have to do slideshows.”

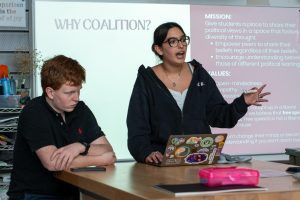

Distance learning forces teachers to be less flexible with their lesson plans, according to Ms. Owens.

“I have to put so much time and effort into getting things up on Schoology that once they’re up there, I’m kind of just, ‘We’re probably going to stick pretty closely to this,’” Ms. Owens said. “I definitely feel like in order to maintain my sanity, I can’t be as flexible as I usually would be.”

Despite the increased work demand, French teacher Jean-Franklin Magrou has found some advantages to distance learning such as reduced distractions.

“When we are in the building, teachers are bombarded by all kinds of tasks, by all kinds of emails and things to do throughout the day that kind of pulls them away from the actual lesson planning,” Mr. Magrou said. “That is not so much the case this year.”

To deal with the difficulties of distance learning, many teachers participated in professional development, and, according to Mr. Magrou, the world languages department meets regularly to consult one another.

“We have been talking about the use of technology, and every month we have a conversation about ways of maybe streamlining things, making them easier for the students and for teachers,” Mr. Magrou said.

Technology is also a topic of discussion in the math department, where department meetings were weekly but have just switched to every two weeks, according to Ms. Anderson.

“I feel very lucky to be in the math department because anything that anybody learns, they’re willing to share it with each other,” Ms. Anderson said. “We actually have tech talk with Ms. Lunte. Because Ms. Lunte’s really good at technology, and so she will take us through stuff.”

Despite attempts to make remote learning easier on teachers, Dr. Hund finds distance learning inherently less rewarding.

“It’s tough because it’s not stuff we enjoy as teachers, or, at least speaking for myself, I don’t enjoy it,” Dr. Hund said. “I’m spending so much time on my computer — and not necessarily on Zoom, not necessarily talking to students — but just simply organizing information, and it really isn’t enjoyable. It’s not why I went into teaching.”