Jewish leaders work to strengthen social justice in Chicago

Rabbi D’ror Chankin-Gould and Cantor David Berger have very different experiences from working on opposite sides of the city.

March 2, 2021

The 2020s so far have paralleled the later years of the 1960s — both are periods of racial inequality, newfound perspectives and social activism. Something especially positive about the ’60s was the interracial alliances that developed, such as the partnership between Black and Jewish people. Amid the civil rights protests, Jewish and Black people marched together in the streets and supported one another’s rights to equality. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. even formed a long-lasting friendship with Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel.

The protests that unfolded last summer also echo the movement from decades ago — again, Jewish activists are fighting alongside Black activists for change.

Rabbi D’ror Chankin-Gould and his husband, Cantor David Berger, both contribute to social justice work for Black communities — particularly as racial tensions have escalated in the past few months — each influenced by their synagogue locations on opposite sides of Chicago.

Rabbi Chankin-Gould works at Anshe Emet Synagogue in Lake View, and has both organized and taken part in many of the congregation’s civil rights projects. Anshe Emet has a close relationship with Bright Star Church, a predominantly Black church in the Grand Boulevard neighborhood on the South Side. The two places of worship often team up to teach their members about oppression and help connect the two groups.

“I’ve tried to define more virtual opportunities to continue to partner together and share the work that we do,” Rabbi Chankin-Gould said.

The rabbi acknowledges Chicago’s divisions and said people in predominantly white neighborhoods such as Lake View have the responsibility to help bridge the gap between the two sides of the city. According to the rabbi, partnering with Bright Star has allowed him to educate others on the city’s different neighborhoods.

“Chicago is very segregated, which means that people are often not encountering others who have very different experiences from their own, which is very dangerous,” Rabbi Chankin-Gould said. “So we have to embrace opportunities to come together, even if it’s not easy.”

Rabbi Chankin-Gould and Cantor Berger have two adopted sons, one Black and one biracial, who they say is a cause of why they are personally invested in the fight against racism.

“In a way, it’s always been very personal,” Rabbi Chankin-Gould said. “I feel very fearful about what could happen in my mind, right now, with police brutality and police violence.”

Rabbi Chankin-Gould said another motivating factor for him was the rich history of Black and Jewish people supporting one another, which has become lesser-known over time. According to him, there have recently been misunderstandings and disputes between Jewish and Black people about the Black Lives Matter organization — rather than the movement’s — stances on Israel. This has made some Jews unwilling to help the movement as a whole.

“It’s wrong. We don’t have the right as people with so much privilege to take one issue and turn it in the other direction,” Rabbi Chankin-Gould said. “I hope I can inspire others to say, if they’re feeling anxious about engaging because of their concerns about Israel, that’s a reason to open a conversation.”

Christie Chiles Twillie, Anshe Emet’s choir director and a member of its Social Justice Committee, also believes the Black and Jewish communities need to support each other. A person of color herself, she and Rabbi Chankin-Gould have had open conversations about topics involving race and equality.

Ms. Twillie says her background has prompted her work and motivated her to continue bridging the divide between Black and Jewish people.

“I’ve been involved in discussions centered around social justice with Rabbi D’ror,” Twillie said. “In many ways I put myself in a vulnerable position so that people can feel comfortable asking questions.”

Twillie said that collaborating on these types of projects force her to put herself out there, which is necessary so that Black and Jewish people can learn about one another and see their similarities.

“We are both communities that care deeply about our families,” Twiles said. “We also both have long histories of speaking up for others, standing up for others, even in the most difficult of times.”

Twillie said that the work Rabbi Chankin-Gould is making her more open to having these types of difficult conversations, and the work is bringing to light people’s personal struggles with prejudice that aren’t as widely-spoken.

Cantor Berger, working on the South Side, has also contributed to different projects to help the racial injustice in Chicago. He cantors at KAM Isaiah Israel Congregation in Hyde Park. One of only two synagogues on the South Side, KAM Isaiah Israel has made a significant effort to educate its members on civil rights, including bringing in speakers and working closely with activism organizations. Cantor Berger and his synagogue have taken advantage of their location to immerse their members within the Hyde Park community and educate them on issues they face.

“We’re also asking ourselves, ‘What is our own racism?’ and ‘What are the ways in which we fail?’” Cantor Berger said.

To educate members further, Cantor Berger and his synagogue have also connected with the South Side police and hosted lectures about police accountability. The synagogue has also brought in social justice activists to talk to congregants, such as Jesse Jackson, whose nonprofit civil rights organization Rainbow PUSH Coalition operates at KAM’s former building.

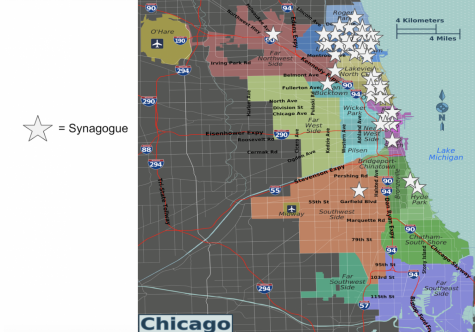

As someone who’s spent a lot of time in South Side neighborhoods, Cantor Berger said the community has given him a more well-rounded perspective on the differences between the sides of the city. Cantor Berger said his synagogue is very diverse, encompassing several Black Jews and Black family members of white congregants. According to Cantor Berger, while Chicago’s synagogues used to be all over the city, they have all moved up to the North Side over the years, leaving him with a connection to Hyde Park and its residents that is much more personal than most synagogues.

“In my synagogue, we’re not just talking about a group of people, we’re talking about ourselves,” Cantor Berger said. “There’s lots of Jews of color at the synagogue, so topics of racism are not theoretical to the people around us.”

Cantor Berger said it’s important to note that, despite his close affiliation with many Black people, he will never be able to be in their shoes and never tells people how to feel.

“Despite our diversity, many of us still are, primarily, white people who make mistakes,” Cantor Berger said. “And we’re taking that very seriously as a congregation, and bringing in trainers and doing real work to improve.”

The synagogue’s physical location has also enabled Cantor Berger and the congregation to have more direct access to volunteer sites in Hyde Park. KAM has even been able to create a nationally-recognized program, a “Farm and Food Forest School,” that teaches volunteers about food justice and sustainability, as well as how marginalized groups of people are often left out from receiving proper nutrition. According to Cantor Berger, the garden plants are delivered to nearby food pantries.

Working on opposite sides of the city shapes the couple’s efforts and their connection to the topic of racism and social justice, but Rabbi Chankin-Gould and Cantor Berger both feel that, regardless of differences, it’s important to maintain a united front.

Cydney Wallace • Mar 9, 2021 at 7:21 am

There are THREE synagogues on the South Side of Chicago and I find it disgusting that an article about social justice and repairing the bridge between Blacks and whites (ESPECIALLY in the Jewish community) would erase Beth Shalom B’Nai Zaken Ethiopian Hebrew congregation from the conversation.