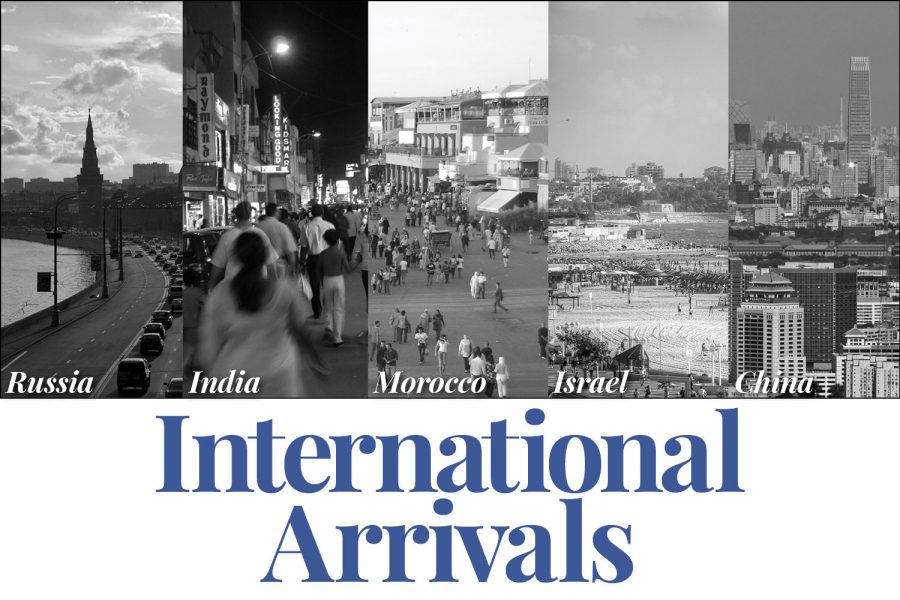

International Arrivals: Immigrant students face increased scrutiny, reflect on America

May 10, 2018

These students are from all over the world — from China to Morocco, they came to the United States later in life.

Junior Sammer Marzouk, who moved from southern Morocco to Chicago in 2012, was a member of the nomadic Tuareg tribe. School was mandatory up until fifth grade, but he continued beyond the requirements.

Sharanya Srinivasan was born in Hong Kong but moved to India at age 2. After living in India for 14 years, she moved to Chicago and began her time at U-High as a junior.

After her father was sure her family would be moving and their visas were fully processed, Sharanya, now a senior, was given three weeks to say goodbye to her friends and to her life in India before she immigrated to the United States.

Junior Eva Massey moved from Moscow to Chicago when she was 13. Because her father is American and she visited him often before the move, the transition was smooth.

Hongjia Chen lived in China until age 11 but started sixth grade in Chicago at the St. Therese School, a Chinese Catholic school in Chinatown. Now a junior, he began at Lab as a freshman.

Yael Rolnik, a junior, was born in Israel, living there until age 12. She then moved to Boston, and two years later moved to Chicago.

Cultural adjustment

Socially, adjusting to American culture was a double-edged sword for Sharanya.

“I think adjusting to the culture was good and bad in some ways. It was good in that it was way calmer than I expected it to be,” she said. “I expected it to be more ‘Mean Girls’-esque but it was not. Lab is a very welcoming environment as is my class in particular.”

Still, she found it difficult to fit into Lab’s friend groups which, it seemed to her, had been set in stone since nursery school.

“It was difficult in that a lot of Labbies have been here all their life and are set in their friend groups and social dynamics, which I had a rough time sort of integrating myself into,” she said, “but I finally found a very welcoming group of friends who accepted me and now treat me like I have also been here for years on end.”

Chen’s Chinese Catholic school experience served as a bridge in his transition to America.

“Most of the students there are Asian-American, and even though I was still learning this new language, sometimes I could talk with them in Chinese, and sometimes they could translate,” he said. “When I didn’t understand something they could explain, you know instructions from teachers and stuff like that. So the transition was made much easier by them. And I really appreciate them for that. But I imagine it would be really difficult otherwise.”

Chen found that the most difficult part of his transition was learning English, noting it took him about a year to fully understand what his teachers were teaching.

Sammer’s typical day in Morocco was quite different than now.

“On a typical day, I would wake up at 5-6 and go to the mosque for the morning prayer. Then I would go tend to the cattle and move with the tribe. At 10, I would go to school. At 1, I would go back home for the afternoon prayer and help my family. At 2, I would go back to school until 5.”

He moved frequently, given his family’s lifestyle.

“The amount we traveled throughout the day was never consistent. It was based on the terrain and any government action or boundaries. Also, in middle school, a lot of government restrictions were set up to end nomads. That was when I moved to America full-time.”

Educational change

The educational system in Morocco is drastically different than that of Lab. It was even more different for Sammer because, as part of the nomadic Tuareg tribe, he moved frequently.

“Before I lived in America, I didn’t go to a physical school. It was more of a roaming tent school, so there wasn’t a set place. You’d just sort of learn whatever you wanted to, but there was this one big test at the end of the year that you would have to take to go up a grade level,” he said. “But at Lab school and I guess all of America, you have to show up to class and you’re required to and there’s not just one big exam that determines if you pass.”

According to Sharanya, Lab has a much more exploratory and thinking-based educational system. In India, education is much more theoretical.

“For example, I had never written a research paper in India. That wouldn’t be an assignment in India,” she said. “It would be more question/answer-based versus outside of strict classroom material research.”

Like in India, China’s educational system is mostly fact-based. Chen explained that Lab’s educational environment is drastically different from his school in China in terms of ethos.

“Just in general American education values freedom and creativity, critical thinking. I guess the teachers guide you. They don’t force you to believe something. In China it’s a little bit different,” he said. “Partially because the language is structured differently. When you say something in English you can hear the vowels, hear the sound, and write it down. In Chinese, it’s different. You have to memorize the characters and how they appear. So there’s a lot of memorization in the Chinese education. It’s just a different style of teaching.”

A stark change for Eva was adjusting to the more capitalistic educational system.

“Everything in Moscow is state-funded — I think most places in Europe are like that — so I went to a state-funded music school, and state-funded schools are a lot better than the ones here,” she said. “I think that was difficult. I actually ended up quitting the flute because there I graduated from music school, and it was very interesting and nice, and it was my place. But here private teachers are the main way to learn anything outside of school. That was something that annoyed me a lot. There is no sense that children should learn music and it should be free.”

Xenophobia

As a student from another country, Chen reflected on American xenophobia, attributing it to national pride. According to him, there is xenophobia in China as well. However, he finds it particularly odd in the United States as its culture is based on immigration.

“I think America is very different than any country in the world because practically the first people who came were refugees,” Chen said, “so I don’t know why they get to set the standard if you know what I mean. Like, why do their traditions and cultures — why is that the standard we need to align ourselves to?”

For Yael, the United States lacks the sense of community she was familiar with in the much-smaller Israel.

She added, “I feel like Israel is so small it’s easy to get kind of blinded and focus more on what’s happening in Israel because it’s like it’s not a part of something bigger.”

Because of this, Yael found she wasn’t too aware of politics during her time in Israel.

“I think that with the Palestinian-Israeli conflict — living there from when I was born to age 12 — I wasn’t very aware of it. I knew it was a thing but I didn’t know the specifics. And then when I moved to the United States and especially at Lab I’ve dug deeper into it.”

Recently, she and junior Jamal Nimer, whose family is from Palestine, used the Social Justice Week platform to discuss the Israeli-Palestine conflict.

Since entering the Lab school community, Yael has become involved with other social justice issues as well, such as women’s rights and gun violence, finding that creating a sense of social justice and unity is key to fighting xenophobia.

Reflecting on her immigrant status, Sharanya noted that she almost forgets she is not a citizen when in the Lab and Hyde Park bubbles.

She said, “But it hits me when I have to do things like get a driver’s license or go to a place that is not as accepting of international students or when I start to think about things I want to do but am immediately reminded that I cannot do them because of my visa.”

MADALO • Dec 25, 2024 at 6:30 am

Welcome back home Eva! I still remember you 20 years later… Your “Au Pair”. Madalo