Weighted Words

As political conversations have grown to be increasingly polarized, discussion is often unattainable

Tosya Khodarkovsky

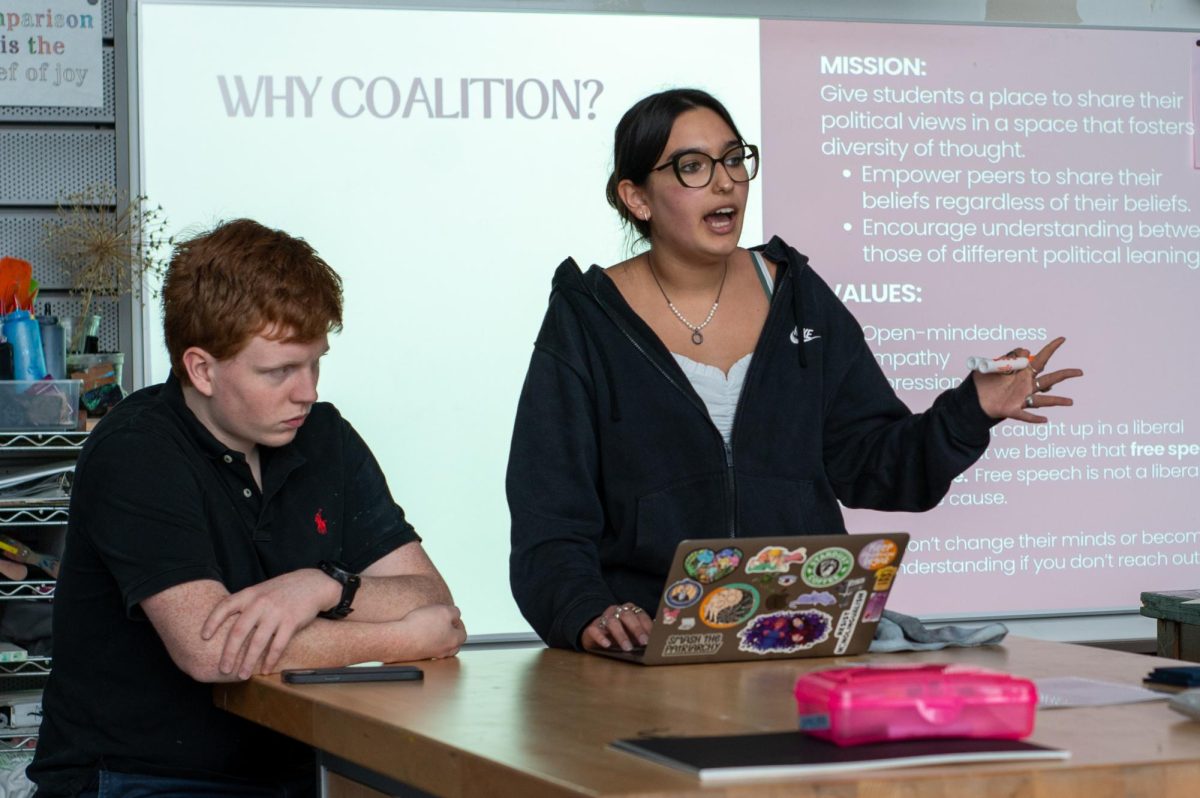

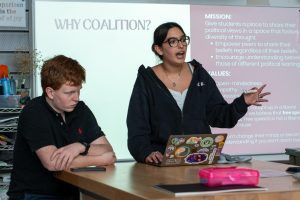

FOSTERING DISCUSSION. Izzy Knowles, Michael Harper, and Addy Maciak, seniors, talk during a meeting of Feminist Club. Sally Carlstrom, a senior, and one of the leaders of the club, often worries that if a point she found offensive was brought up in a club discussion, she might not respond in the way she would like to. Respectful disagreement is a cornerstone of Feminist Club.

October 12, 2018

Professor Anna Mueller collected data at a school with a rigid, widely-known definition of what it meant to have a good family or be a good kid. She said it made for “a really intense place for kids who deviate from those expectations” because parts of their identities were rejected by a place they couldn’t escape.

It’s a general consensus within the Lab community that this definition involves liberalism. And the polarization of U.S. political ideology has penetrated Lab’s bubble, making it especially difficult to have conversations about politics or controversial topics, according to many students. The consequences for saying the wrong thing could be damning, but some club leaders say it’s worth trying to bridge the divide.

Senior Mitch Walker said he finds this environment frustrating.

“One of the biggest things for me with discussions at this school is that a lot of the times I feel as if — and I’ve experienced this [in conversation] with my friends — that they’re afraid to speak up not because they’re afraid to be disagreed with but because they’re afraid that what they’re going to say will be interpreted in an incorrect way, or that people will interrupt them before they can finish a thought, and bend their words,” Mitch said.

It’s hard to have ideological debates in the current political climate without the conversations being weighed down with connotations, according to Dr. Mueller a sociologist and professor at the University of Chicago’s department of comparative human behavior.

“Political conversations are so laden. If you were to debate the Supreme Court nomination right now, you would not be debating conservative versus liberal,” Professor Mueller said. “It would be a debate laden with ‘Do you believe women who have survived a sexual assault,’ or ‘Do you believe men who may be falsely accused,’ and that’s an impossible debate.”

These issues are especially difficult to discuss because of the “heightened emotions” around them, Professor Mueller said. “When people are emotional and being hurt by really powerful people, it’s hard to just be completely calm and cool and just listen to the other side.”

During a discussion, Sally Carlstrom, a leader of Feminist Club, said if someone made an offensive comment during a club meeting she hopes she would take them aside to have a one-on-one discussion. But that’s hard to do.

“As a leader, I would try really hard to respond calmly. But I know it would be difficult for me not to break out into anger,” she said, “and I feel like anger is a valid emotion.”

Sally said she wants as many people as possible to come to Feminist Club so the community can benefit from discussion of difficult issues. But she doesn’t want to stifle voices as a result.

“For a lot of girls, we are trained from a young age to not use our voice and take up as little space as possible. I just want to create a space where our voices are valued and heard — and I also want to include other people,” Sally said. “For me, Feminism is about equality throughout the gender spectrum.”

It’s a balancing act that U-High Conservatives Club member Michelle Tkachenko Weaver said her club also wrestles with.