If you’ve been at Lab long enough, you’ve probably sat in class where students are discussing what are often referred to as sensitive topics. Many of us are used to that awkward silence in a Harkness discussion where no one wants to say “the word.” Whatever “the word” may be varies from course to course, but one thing remains the same: students are reluctant to speak up against injustice for fear of being labeled divisive.

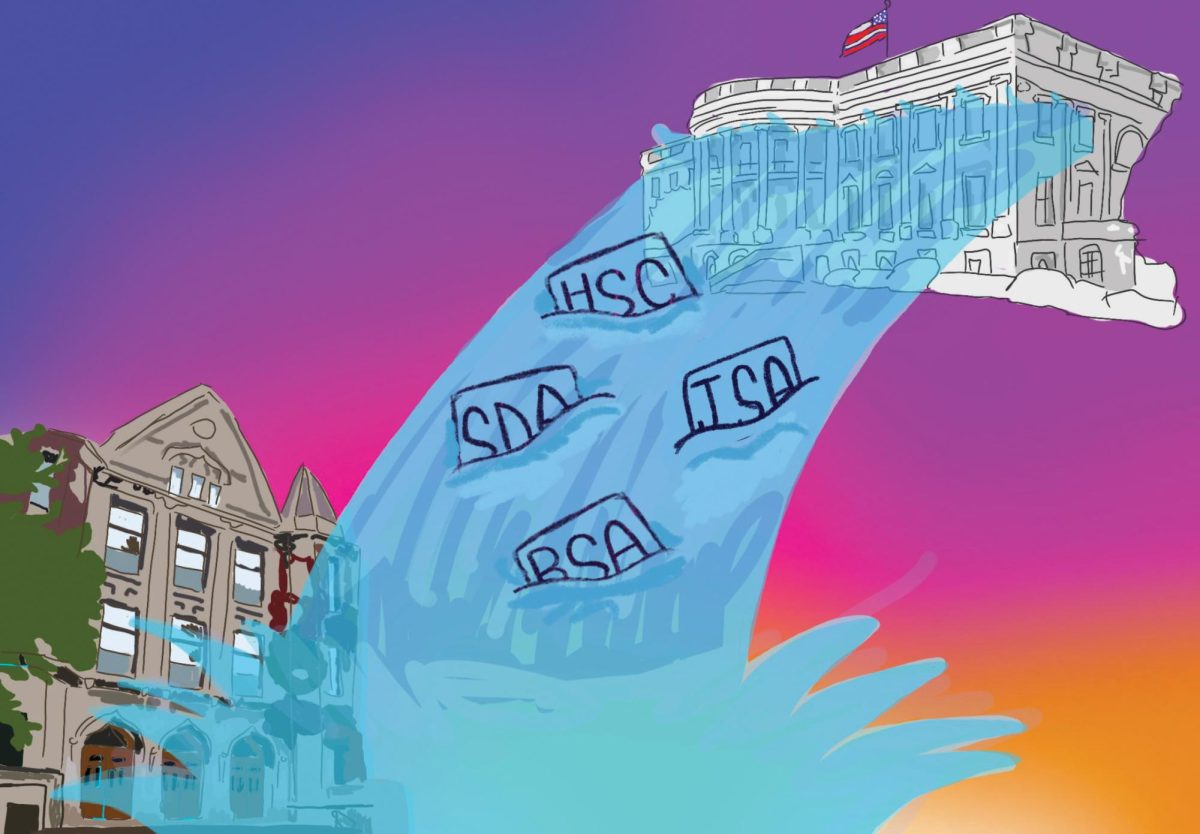

Recent protests occurring on university campuses across the country in response to the war in Gaza are an extreme example of how student activism can manifest. And it’s not the first time foreign affairs have bled onto U.S. college campuses. Just over 50 years ago, students at Columbia University and Barnard College protested the Vietnam War, shutting down five campus buildings in the process.

For many U-High students, college is not a distant dream — it’s our near future. We students must be willing to engage with conflict and understand how to confront conflict while at a university.

Students commonly misunderstand their First Amendment right to free speech. Though students have a constitutional right to free speech, with minor exceptions, public and private universities have the right to put restrictions on how speech is used in public spaces on campus, so long as the restrictions are applied equally. Understanding how to confront conflict relies on student knowledge of an individual’s action, such as breaking the law.

Colleges and universities with large platforms and spaces for student activism pose a unique challenge for U-High students.

Alexander W. Astin writes that civic engagement has declined in part because higher education institutions have prioritized educating the next doctors, lawyers and scientists and seem to have forgotten the chief duty of civic responsibility. These institutions educate students who recognize racial disparity, social inequality and economic issues as pressing topics, but without a foundation of citizen engagement, there’s no logical path forward toward resolution.

That said, according to an article by Margaret T. Brower and J. Kyle Upchurch, universities and post-secondary institutions are better equipped to support students when they promote student activism on campus. Dr. Brower notes that “equitable activism” can be obtained in addition to equalizing power by being courageous enough to say what’s contentious. U-High students have to embrace discomfort.

Normalizing challenging the ordinary — or rather the status quo — doesn’t inherently weaken the institution’s prestige, it allows its mission to come into the present day and become a more equitable learning space. Students can be a part of the solution, using methods of dialogue, without fear of dissent.

One thing is clear: the unique space reserved on a college campus for student activism is a shared responsibility between the administration and students. Ms. Brower notes that how campus administrators respond to events of protest shape the way students engage in activism moving forward.

In addition to the administrative responsibility to foster an environment that encourages collaboration between students and university leadership, students should understand equity principles and civic responsibility to reimagine the campus democracy they wish to take part in.

S. Williams • May 3, 2024 at 10:21 am

Protests regarding the Vietnam War took place at many more campuses than just Columbia and Barnard. This protest conversation is incomplete without including the protests against apartheid and calls for divestment in South Africa. This is a good start to conversation – I wonder how we can begin this work at Lab?