Learning to deal with distractions

Learning coordinators create individualized plans for students

Isabella Kellermeier

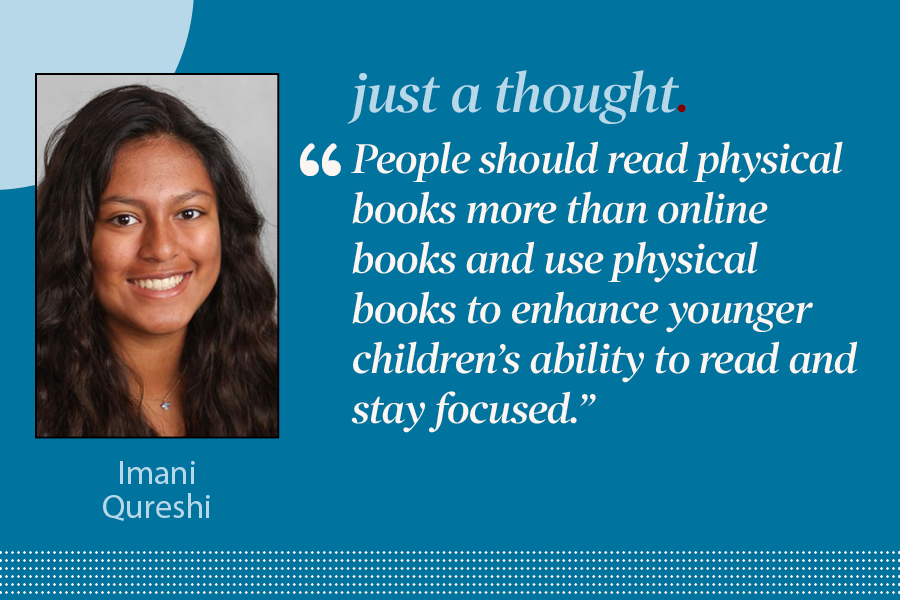

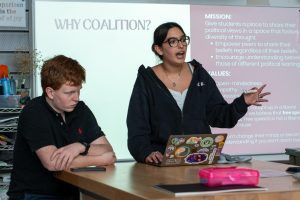

BUILDING COMMUNITY. Junior Elizabeth Gately sits down with learning coordinator Lesley Scott to pick out courses for senior year. Learning coordinators often help students develop plans for their education. From test taking strategies to arranging extra time for students during tests, learning coordinators aim to provide students with the resources they need to succeed in their classes.

January 25, 2019

“When I was in first grade, there was a student in my class who acted out all the time and who was always in trouble. It was very obvious to me, all of six years old, that he was having trouble learning,” Laura Doto, a learning coordinator, said. “It wasn’t that he was bad, he just couldn’t sit still and he couldn’t do the work and he wasn’t doing the homework and his name got put up on the board basically every day. And I just never thought that was very fair.”

Although Ms. Doto said that she has always been good at learning, she never expected that she would become a professional educator.

Now, as a learning coordinator, she works to figure out what accommodations would be most useful for students who have learning disorders.

Ms. Doto, who is new to U-High this year, and Lesley Scott, U-High’s other learning coordinator, help students develop good practices, such as becoming more organized or developing effective testing strategies. According to Ms. Scott, accommodations for students might include extended time or use of the testing room, where a student who has difficulty with reading comprehension might read questions aloud.

But the learning coordinators don’t just help students with learning disorders.

“For a student with a mood disorder, the more concrete the plan, the less likely they are to get worried about it because they’ve got some consistent opportunity,” Ms. Doto said. “There’s some certainty.

Oftentimes, the act of planning, for students with a mood disorder — it’s not that they don’t know how to do it, it’s creating the space and time to do it so they can actually act and not get worried.”

Anyone can ask from help from the learning coordinators, Ms. Scott said. They often act as mediators between students, parents and teachers — Ms. Doto calls this “educational diplomacy” — and will help any student who stops by.

Ms. Doto said she never expected to find herself working education.

“My mom had been a teacher, I was like, ‘Nope, don’t want to be a teacher, I want to do economic development in Latin America,’” Ms. Doto said.

But one way or another, education has always found its way into her life. Ms. Doto went to the University of Chicago for a master’s degree in Latin American studies, and ended up getting her degree in the effects of a bilingual education in the Chicago Public School System. Despite majoring in Spanish and History, and ended up doing quite well on the National Teacher’s Exam.

She is now dedicated to education counseling.

When a new student comes by, the learning coordinators will establish rapport, understand the student’s process, then try to find the root causes, according to Ms. Scott. If, for example, a student needed help writing an English paper, the learning coordinator might help the student write the skeleton of an outline.

“So when they start that work then later in the day, whether it be during the school day or at home, they’ll have that jumping off point,” Ms. Scott said.

The learning coordinators said they help any student who comes by as best they can.

“If you can cross my threshold and have an honest conversation about where you are,” Ms. Doto said, “I will get you somewhere. You just have to show up and I’ll take it from there.”