Teach passion for learning, not toxic competition

April 24, 2019

It’s not just some ideal, that all people should love to learn and think. It is a useful skill for the direction our economy is heading.

Ted Dintersmith traveled across the United States for a school year, visiting 200 schools of all types and convening 100 community forums to write his book, “What School Could Be.” In it, he argues that “machine intelligence” has reshaped the skills necessary to thrive.

“Our education system is stuck in time,” he writes, “training students for a world that no longer exists.”

Lab should be preparing students for what the world will look like, but the school’s dangerously competitive culture is hindering progress. Competition is important and can provide motivation for students, but taking competition too far makes for a toxic atmosphere and hurts students’ ability to retain information and enjoy learning for the sake of learning. This is in direct opposition to the purpose of an educational institution, especially in the face of a changing world.

Innovation, creativity and big ideas are becoming more and more important.

Forcing students to “jump through hoops and outperform peers, hollowing out any sense of purpose,” Dintersmith writes, is counterproductive.

Education should be enriching us, not burdening us, and according to the Health and Wellness Survey administered in spring 2018, 94% of Lab middle and high school students reported schoolwork to be one of their top stressors. I have friends who get four hours of sleep per night in order to keep up with extracurriculars, homework and tests. This is not a routine that encourages learning or thinking or innovating, and it’s the result of an environment which prioritizes grades and résumés over real skills.

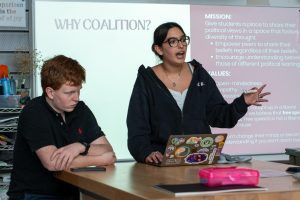

Lab — students, teachers, parents, administrators — should be exploring ways to actually prepare its students for success. What can Lab’s curriculum do to actually help prepare students for the world, instead of allowing the college admissions process to dominate? Could we have classes generating creative solutions for climate change, or innovating the next big social media platform?

If any school were to ask the questions, to push back on assumptions, it should be Lab. We have money, dedicated staff, a prodigious reputation and a research university. Why aren’t we acting now?

When I walk through Gordon Parks Arts Hall, I am greeted by blank, white walls and gray pillars. It’s not inspiring or motivating but institutional and depressing. It should be filled with massive art pieces, the walls covered with murals. It would serve as evidence of our creativity and drive further innovation.

Lab needs to take full advantage of its space. The opportunities are endless. There could be model-rocket launches in Scammon Garden every Saturday, and frequent school-sponsored trips to different neighborhoods on the South Side.

Dintersmith lays out four principles in which students thrive: purpose, a reason for learning; essentials, development of skills necessary for innovation; agency, self-direction and motivation; and knowledge, retention of information.

Lab checks all the boxes. It sends its students to great schools, nurtures passions and broadens minds.

The outdoor classroom, murals on the third floor and makerspaces are all steps in the right direction. But Lab still offers courses which have an end goal of test preparation — and students compare too much. We must do more than simply funnel students into top colleges and universities. We must provide students with the tools they need to succeed.