Teachers adapt assessments to promote academic integrity

U-High teachers have been experimenting with new assessment formats that discourage cheating by challenging and engaging students.

November 9, 2020

Generation Z knows its way around the internet. In just seconds, most U-High students could pull up any number of obscure facts and formulas, deftly navigating the sum of man’s knowledge on a screen around the size of your average textbook. Teachers face a unique challenge during distance learning: how to discourage cheating when endless information lies directly at students’ fingertips.

As traditional tests cannot enforce academic integrity during distance learning, U-High teachers have been experimenting with new assessment formats that discourage cheating by challenging and engaging students.

With the closing of the school campus last spring, teachers had to modify test protocols to a virtual format. History teacher Christy Gerst narrowed the scope of the content on her AT European History class’s essay tests and allowed students to take them asynchronously using class notes.

“We tried to take away that kind of competitive fervor around a test and instead sort of focus on why we do what we do,” Ms. Gerst said.

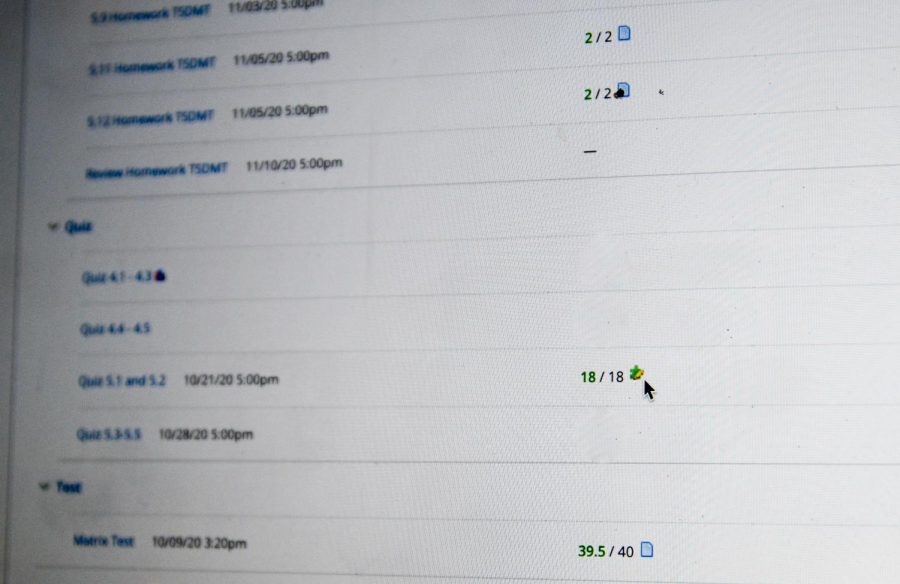

Math teacher Jane Canright avoided giving out tests altogether, opting to instead assess students through problem sets and quizzes. This fall, though, her classes take synchronous tests. In her Trigonometry, Statistics and Discrete Math Topics class, Ms. Canright allows students to reference notes during tests, a strategy discussed during a summer professional development course she took through One Schoolhouse.

“In TSDMT … we are allowing those students to use their notes. Just as a way to kind of, you know, maybe alleviate the stress a little bit but put everybody in the same boat,” Ms. Canright said. “You know, everybody can use their notes and they won’t be as likely to want to use other resources.”

Ms. Gerst participated in the same professional development course. What she learned in the course led her to focus this year’s tests on critical thinking, requiring a student to engage with the material beyond straightforward, searchable answers.

“In history classes, we’re asking you to work as a historian, and we introduce you to all these ideas like contextualization and sourcing and periodization and point-of-view,” Ms. Gerst said. “You really look at a test as a way in which you’re practicing and that it’s about developing your own voice and your own perspective and your own scholarship and expertise as opposed to there’s some sort of set information that you need to learn.”

Sophomore Charlie Benton, a student in one of Ms. Gerst’s AT Modern European History classes, in-depth, open-note tests take away the temptation to cheat and help him better understand the material.

“It’s not like memorization. It’s like practicing what we did in class and putting what we learned to the test, as all tests should be,” Charlie said.

Chemistry teacher Jim Catlett hopes students will avoid academic dishonesty so they can learn the class’s content without taking ineffective shortcuts.

“I know it sounds very clichéed that when students cheat, they hurt themselves, but it’s a cliché because it’s true,” Mr. Catlett said, “and students aren’t doing themselves any favors by looking for ways to not be honest in the work that they submitted.”

Teachers say they plan to continue to experiment with new assessment methods as classes adjust to distance learning curriculum.

“We feel like we’ve all decided on something we’re going to try,” Ms. Canright said. But that doesn’t mean that that’s the way every test will be for the whole year because we will evolve, and things will work and not work.”