Four male-identifying members of the U-High community sat down for a discussion about masculinity. Responses were edited for clarity and length.

We’re in a moment where people are talking a lot about masculinity. What does masculinity mean to you?

George Ofori-Mante, senior: I don’t even know. I think it’s something that most people have an intuitive understanding of, but no one can really define it. I feel like people would have similar answers if you said, “What is femininity?”

Whit Waterstraat, junior: I think I have to look back to who I looked up to when I was a kid, because that is who I strive to be and a lot of masculinity played into that. I watched a lot of YouTube growing up… DanTDM, Stampylongnose… I had no idea what was going on in their life outside of that, but I knew when I got home, there would be a video there, and it would make my day. So when I think of masculinity, I think of the people who showed up every single day and put all of that personal stuff away from an audience and were able to show up and just be there.

Ares Cajas, ninth grader: I think it’s unfair to define masculinity by one thing or one character trait, or like a couple character traits. It’s different for everybody and the circumstances they’ve been in.

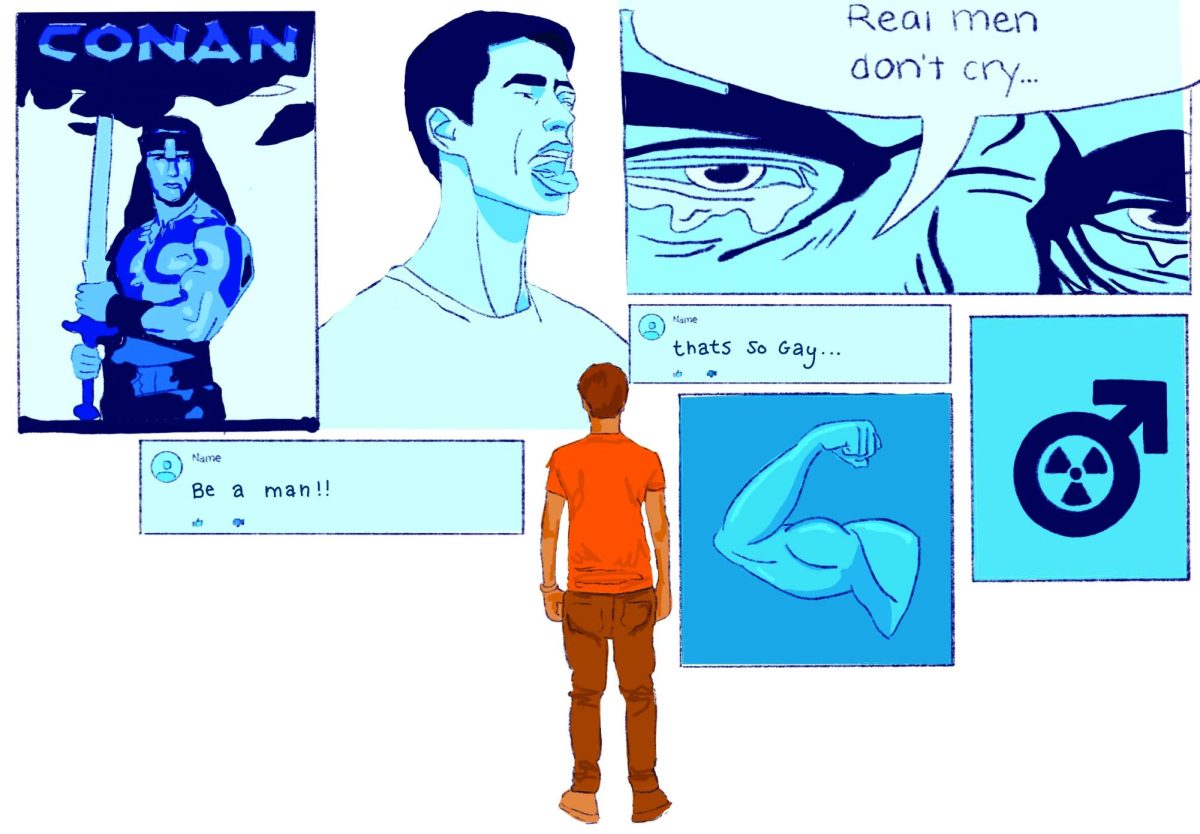

Teddy Stripling, counselor and adviser to Young Men of Color club: I keep thinking of the [role] models that we’ve had. A lot of that I got from my father or my uncles, or like people that I watched on TV, because we didn’t have YouTube back then. Stereotypically, if you’re masculine, you have to have big muscles and be real strong. I’m an ’80s baby, and so I’m thinking of, like, “Conan the Barbarian” and all those other superheroes that were just, like, ripped and running around… those are some of the things that you think of when you think of masculinity, like, ‘Oh, I have to be strong. I have to use force’ or ‘I have to save people.’

Tell us about your experiences surrounding perspectives on masculinity at Lab. How has that shaped your understanding of masculinity?

George: I don’t think there are many conversations about masculinity at Lab to begin with, so I don’t think that really shaped my perspective that much.

Ares: I feel like the emphasis on it is kind of not as prevalent at Lab as other schools. In my experience, Lab has a lot more spaces you can fit in, because of the offerings it has. So I feel like there’s not as much emphasis on defining masculinity.

Whit: Growing up at Lab, there was a lot of talk about sexuality more so than masculinity or femininity. Sexuality was at the base of it all. For years, I was in a world in which people would just be like, “Hey, are you gay yet?” So I was always questioning my sexuality and nothing was coming from it. I felt a lot of my masculinity was stripped away from me because people put this defining feature that wasn’t representative of me in the forefront of their minds. And therefore it took a long time for me to have a conversation with myself and figure out who I am, what masculinity means to me, who I want to be, and escape this idea that other people get to define me.

Do you think about yourself through a lens of masculinity? In what ways yes and in what ways no?

George: I guess I present masculine. I think that’s one aspect of it, personality-wise. I can be more competitive in some aspects. But I feel like beyond that, I think the one thing I don’t like about saying that I present masculine, is having gender roles put on me. I really don’t like having to live up to something because I was born a dude. I think that’s pretty annoying.

Ares: If you look at yourself through a lens of masculinity, you’re just focusing on how other people see you. And personally, I just don’t really like to focus on how other people see me but rather how my actions affect other people and just working to be better every day. I just don’t really like to draw back to the definition of masculinity. It’s different for all people.

Mr. Stripling: I’m a new father and I have a son and so now I’m thinking of all of these questions because I grew up in a different generation where people really pushed a lot of those things on you. I think that’s the thing that I think about for him: how do I give him the space to be a person who can be competitive and at the same time be really communal?

When you think about the term “toxic masculinity,” how would you define it? What do you think about that term?

George: When I think about it, I think of extreme masculinity; you have to be super big and strong, you have to be super loud. I think a lot of people, when they hear toxic masculinity, they automatically think people are just saying masculinity — in and of itself — is toxic, which I don’t think is the case. We have to take care with defining things the right way, so that they aren’t misusing it and the actual concept isn’t distorted into something that it isn’t.

Whit: I don’t know if I’ve ever really heard guys use the word toxic masculinity. It is something that is perpetuated by mostly women — mostly feminists — which is not a bad thing. But I think that a lot of guys hear that and go, “You are challenging who I am and you’re saying that I’m inherently bad for having these traits.” And therefore it becomes more toxic because they close up even more because they don’t like the way that other people are perceiving them. Toxic masculinity is systemic.

Ares: If you’re perceived by others as masculine, maybe it’s just how you grew up. You’re just from the environment you were raised in and maybe you just are perceived masculine. So if you take toxic masculinity, and if it’s over-extended, it can just be more of an attack on who you are and that is not good.

As we wrap up, do you have any other thoughts to share about masculinity?

George: I guess the last thing I would say is that if you’re a dude and you want to be that big, strong, cool guy, I think that’s completely fine. I think guys should also have the choice to be something completely different from that. I think it all comes down to just not being put in the box.

Whit: I’ve been in theater since I was four, and it’s a world that people still make fun of me for, and I have so much fun with it. I would say you don’t have to limit yourself to exploring a passion or something. You might be scared to try because you are worried about the way that other people will receive it, but there’s so much more self-fulfillment that comes out of that than could ever come out of following the line, following what you think other people expect you to do.