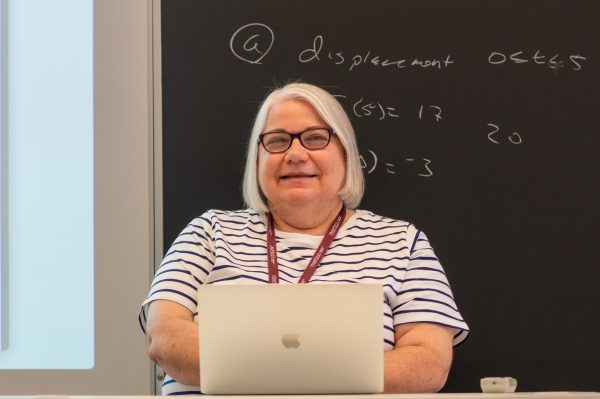

Art teacher facilitates student conversations regarding racism

Sunny Neater has committed to teaching antiracism at Lab. Ms. Neater draws from her teaching experience at schools with most minority students to facilitate conversations about race with her students, while acknowledging the racial demographics of Lab.

April 14, 2022

“Missouri teen shot by police was two days away from starting college.”

“Vigil For Mo. Teen Killed By Police Officer Spirals Into Violence”

These 2014 headlines plastered newspapers and radio broadcasts alike. Their message: an 18-year-old Black man named Michael Brown had been shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, forcing people all over the nation to confront the dire existence of racism in the criminal justice system. Art teacher Sunny Neater was one such person.

On a school morning in September 2014, her first year at Lab, Ms. Neater heard about Mike Brown’s death and immediately wanted to initiate a discussion about him in her Laboratory Schools classroom.

Ms. Neater said, “I learned about [Mike Brown’s death] on the news on my way to school, and I was, like, we gotta talk about this right away, first period. And there was only one Black person in the class and he was a young Black man. It was the first time that I’ve ever had to talk about anything like that with only one Black person in the room.”

Since then, Ms. Neater, who values her students’ uniqueness above all else, has endeavored to create a welcoming environment for all of her students by immersing herself in antiracist work that she believes to be necessary to combat the systemic prejudice against Black, Latinx and other people of color.

Ms. Neater started teaching in Chicago Public Schools in 2003, where she learned the importance of talking about race and became comfortable doing so.

She said, “I came from teaching on the far West and South Sides of Chicago, where the schools were all Black or all Black and Latinx, so when I came here it just felt very different. At those other schools we had conversations about race all the time, and I was always the only white person in the room. So I got very comfortable with my students and my colleagues talking about race.”

When she came to Lab, Ms. Neater found that conversations about race were quite rare, and often uncomfortable. Ms. Neater, ever true to her values, felt obligated to do something about this.

She said, “[I saw] a need for change at Lab and [saw] that it was falling on my Black colleagues to explain to the community what was wrong with how things were going. And I don’t feel like racism is a problem that Black people need to solve, I think it’s a problem with white people.”

She, along with Allison Beaulieu, her co-chair of the fine arts department, are part of WARE, or White Antiracist Educators, an organization seeking to combat racism at Lab.

[I saw] a need for change at Lab and [saw] that it was falling on my Black colleagues to explain to the community what was wrong with how things were going. And I don’t feel like racism is a problem that Black people need to solve, I think it’s a problem with white people.

— Sunny Neater

Ms. Beaulieu said, “She comes from a public school background and so the ease that she has around antiracist work and social justice work comes from that. And so in WARE that’s kinda the stuff that we talk about. She does not ever feel uncomfortable talking about her whiteness and that is a really great thing to show other teachers.”

Outside of WARE, Ms. Neater, who can hardly ever stand to be stagnant, participates in many other antiracist initiatives.

Ms. Beaulieu said, “We run semester-long antiracist courses. Sometimes it’s a podcast or a seminar that we all take together and then have discussion groups, sometimes we read a book, but it’s usually about something or subjects about decentering whiteness. We have asked the school to look at the numbers of the retention rate of Black faculty and folks of color, so we hope that the numbers will show how much antiracist work is needed.”

At a time where police violence and racism dominates the headlines on an almost daily basis, this message is ever more prevalent. And while she does not want accolades for her actions, Ms. Neater can be used as a model to implement future antiracist discussions in classrooms.

“Awards and honors are not for me,” she said. “I don’t give art awards or art honors because I guess it makes me feel weird, it makes me feel like I’m othering somebody, excluding people, not honoring everyone’s amazingness.”

Years ago, Ms. Neater made the decision to spark a conversation about race based purely on a feeling. Her values and background make it not a choice, not an obligation, but a necessity to take action against racism.

She said, “[T]hat was the first time I started talking about race and racial violence and racism and white supremacy with my students, and it just felt like, how could you not?”