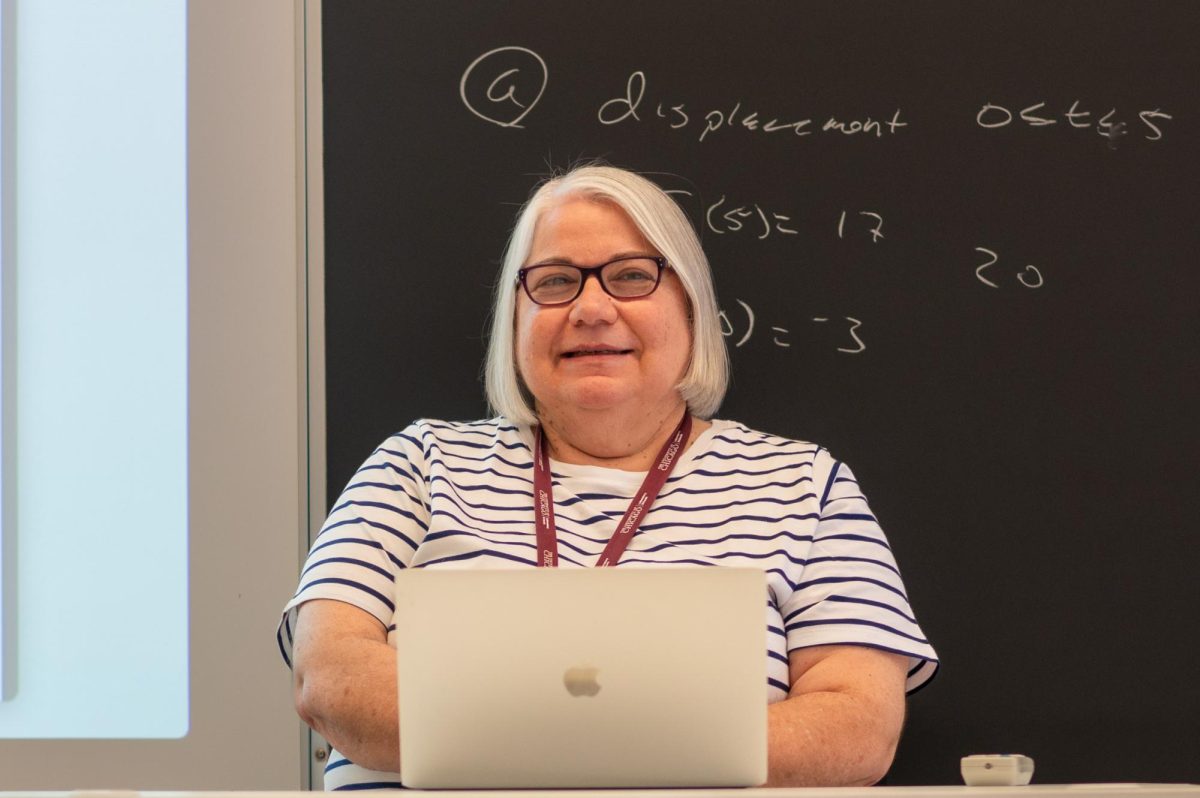

She taught Dostoyevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” and was dazzled by the author’s ability to create characters and build suspense. She brought students Shakespeare and fondly remembers a time ninth graders performed scenes from “Macbeth” interspersed with narratives they had written. She was intrigued by the philosophy of John Dewey, the founder of the Laboratory Schools, who valued experiential learning and the links between education, democracy and art.

But for U-High English teacher Catie Bell, who is retiring after almost 38 years at Lab, it was the people of the U-High community, she says, that will stay with her the most.

“The best part of teaching at Lab School is having students with the capacity for sovereignty and seeking opportunities to exercise it,” Ms. Bell said. “They see connections between what they are learning in class and their lives, and find clubs and other activities in which their hard work is satisfying and rewarding.”

Ms. Bell came to Lab in 1986 as a sixth grade history teacher. She’s lived in Illinois her whole life, growing up in Evanston, studying at Northwestern University and teaching at schools in Winnetka and on Chicago’s West Side. She earned a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 2007.

In those early years, Ms. Bell said the school felt more like a place where most people were from the local neighborhood.

She recalled, “So students, teachers, parents and administrators regularly ran into each other.”

Rules and regulations felt looser then, too, and boundaries were pushed in the name of fun.

“Compared to other neighborhood kids, Lab School students got away with a lot as they exercised their powers of self-regulation,” she said, “often discovering the natural negative consequences of something they had been warned against.”

Ms. Bell, whose scholarship helped her develop a reputation as an expert on John Dewey, said she gravitated toward his writings because she had been a teacher who was interested in experiential education, a central concept of Dewey’s philosophy.

“He saw democracy not as a voting system but as a pattern of associated living where people become individuals by sharing and evolving their unique dispositions and capabilities,” Ms. Bell said. “Importantly, they learn to think for themselves in the community. Their thoughts matter.”

Ms. Bell said she has loved working with teacher colleagues in the English Department through changing times and difficult challenges.

“Together, we have worked diligently to cast a wider net, incorporating literature that students can more easily identify with, coming to grips with the diminishment of reading as a pastime and otherwise coming to terms with teaching the humanities in the twenty-first century,” she said.

Ms. Bell’s students, too, left her with a meaningful legacy, she said.

“Students have helped to free me from ideas derived from static binaries,” she said. She added, “Class discussions have opened me up to appreciating the vast area between ideas we’re accustomed to seeing in opposition, like male and female, educated and uneducated, and lucky and unlucky. Seeing those shades of gray requires hard but valuable work.”

For her next chapter, Ms. Bell plans to split her time between her home in Hyde Park and a home in Cody, Wyoming, where she and her husband have a house outside town, not far from the McCullough Peaks.

“Even after 38 years, I will miss the joy of being around the people here,” she said. “Still, it is time to focus on unread books, spending more time with friends and family, traveling and perhaps learning more about how to live, only minimally diminishing the natural diversity of flora and fauna in the biosphere.”