From pre to post-Roe v. Wade

Service provided women with safe, illegal abortions in Hyde Park

Source: HBO

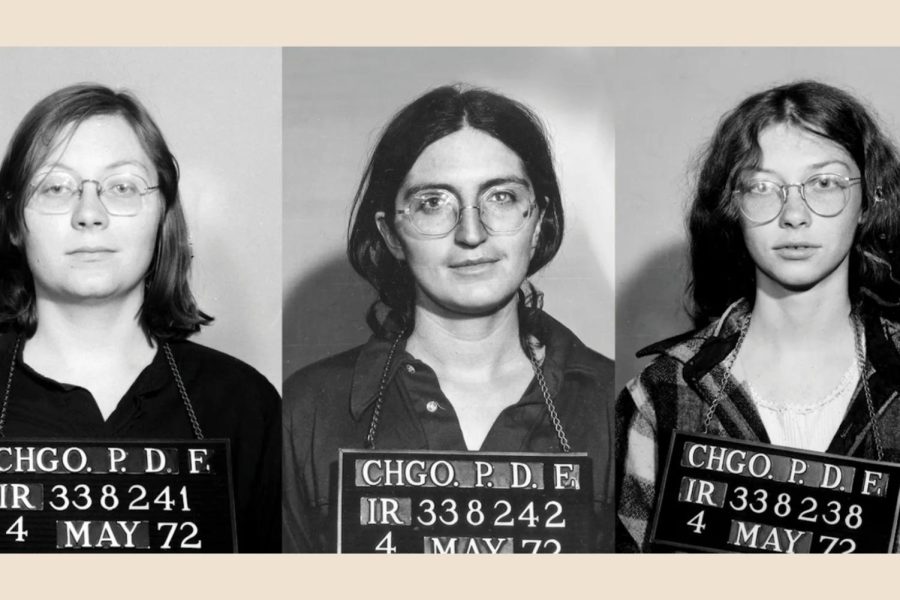

Before abortion became legal in the early 1970s, seven members of the Jane Collective were arrested for conspiracy to commit a felony after getting caught performing abortions. In total, around 11,000 women benefitted from this service.

October 25, 2022

Editor’s note: The six women quoted in this story were interviewed throughout October, either in Hyde Park or via Zoom.

Before the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision legalized abortion nationwide, Dorie Barron, a Chicagoan who was only 23 years old, found herself unexpectedly pregnant with the child of a man who was unemployed, living with his parents and “freaked out.” As a young woman with her future in mind, Ms. Barron said she felt she had no other choice but to have an abortion.

Not knowing what else to do, Ms. Barron put her life in the hands of the Chicago mafia, who quickly arranged for the procedure to be administered in a motel room and left her bleeding. It wasn’t until she had another unwanted pregnancy a couple of years later, that she was introduced to and subsequently joined the Janes.

The Chicago Women’s Liberation Abortion Counseling Service, also known as the Jane Collective, was an organization that provided beneficial counseling and safe abortions to women dealing with unwanted pregnancies in the South Side of Chicago from 1969-73. Despite the legal implications they faced, members of the Jane Collective persevered to ensure the welfare of the roughly 11,000 women they provided illegal abortions to.

“My experience with Jane changed my life,” Ms. Barron said, using a shortened version of the group’s name, “because I had never seen women care about other women and be so kind, be so loving, so protective.”

The service was founded when Heather Booth, a University of Chicago student at the time, heard that her friend’s sister was pregnant, nearly suicidal and looking for someone to provide her with an abortion. The Medical Committee for Human Rights put Ms. Booth in contact with civil rights activist and surgeon Dr. T.R.M. Howard, who performed the abortion.

“I really thought that was the end of it,” Ms. Booth said. “I thought there wouldn’t be a second step, but word must have spread, and I didn’t tell anyone, so it must have been the person who had the abortion. Someone else called, and I arranged for that, and then word must have spread, and someone else called.”

She soon realized she needed to set up a system. After getting informed about the intricacies of the procedure and negotiating prices with Dr. Howard, Ms. Booth decided to recruit other women at various community gatherings to help manage the influx of patients.

The service was soon nicknamed the Jane Collective, when members of the newfound organization created advertisements that read: “Pregnant? Don’t want to be? Call Jane.” The use of the name “Jane” helped those whose phone numbers were displayed on the posters distinguish between personal and professional calls, because if caught, they could be charged with conspiracy to commit a felony.

We wanted to make the women that came to us comfortable. We were not abortionists, we were counselors. We were other women who could get pregnant.

— Eleanor Oliver

“While the Jane grouping did take precautions and was trying to be very careful, we also believed that even in the face of risking your life or your freedom, it’s still important to act for what you think is the morally correct thing to do,” Ms. Booth said.

Once a pregnant woman called for Jane, a member would reach out and schedule a meeting to explain the entire process.

“We wanted to make the women that came to us comfortable,” member Eleanor Oliver said. “We were not abortionists, we were counselors. We were other women who could get pregnant.”

One of the Janes woud drive women who were having abortions from a waiting area referred to as “The Front” to an apartment that was either rented or volunteered. As time went on, core members of the service desired to be more involved with the abortion process. According to member Martha Scott, member Jody Parsons learned the procedure and began teaching others, including Ms. Scott. At one point, Ms. Scott was performing 15 to 20 abortions a week.

“She said this is not something a layperson can’t do,” Ms. Scott said. “This is a very narrow set of information and procedures, and if you are careful and watch what you do, we can do this.”

In 1972, Ms. Scott and six other women were arrested after the police raided their apartment. They were charged with 11 counts of conspiracy to commit abortion, and each faced up to 110 years in prison. The public labeled them the “Abortion Seven.” Ms. Scott described the experience as scary and said she did not expect it.

“It’s not like we didn’t know we were doing something illegal. We knew we were doing something illegal, but we knew that if we chose not to do this, people would be in more trouble than they would be if we chose to do it,” Ms. Scott said. “So I personally did not think very seriously about the consequences because while I thought there was a possibility we would be arrested, I also thought we were kind of protected by kind of a social privilege.”

Jennifer Surgal, whose late mother, Ruth Surgal, was a Janes member, recalled the terror and concern members felt on the night of the arrest, as they walked around with a paper bag collecting cash for the seven women’s bail.

“It was just like all the worst things that you could think of what could happen did,” member Eileen Smith said. “It was really horrifying. And then right afterwards, these people still needed abortions. We had people scheduled for the next day. We had to call them and arrange for them to do something else. I mean, it became so stressful.”

The women’s case was purposefully drawn out awaiting the Supreme Court decision on Roe v. Wade. On Jan. 22, 1973, the 7-2 ruling ensured women the right to an abortion under the Fourteenth Amendment’s “right to privacy,” and all charges facing the Abortion Seven were dropped.

“In a way, I think that the feeling even in very Catholic, very rigid Chicago was, ‘Something’s changing here, and we’re just going to step back.’ So yeah, just mainly relief. Oh, thank goodness that was done,” Ms. Scott said.

Almost 50 years later, Roe v. Wade was overturned on June 24, 2022, when the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

“My heart sank,” Ms. Barron said, “because I know, just as most people who are familiar with what goes on with abortion and what goes on in women’s lives, I’ve lived long enough to understand that lives will be lost and that women are going to be compromised across the board. And sure enough, that’s happened.”

Though abortion rights are protected in Illinois and a ban is not likely, Ms. Surgal said that education and participation in local politics is the key to protecting abortion rights.

“There’s hope when you get people riled up about serious issues, and I want more people to think of abortion as a public health issue,” Ms. Barron said. “It is an issue that has to be called that, and not made to be something ashamed or secretive or behind closed doors.”

Debra S • Oct 30, 2022 at 10:07 pm

Thank you for your excellent reporting in covering this important issue!