Museum exhibit reframes reality through photography

Smart Museum to exhibit images of 1960s Africa

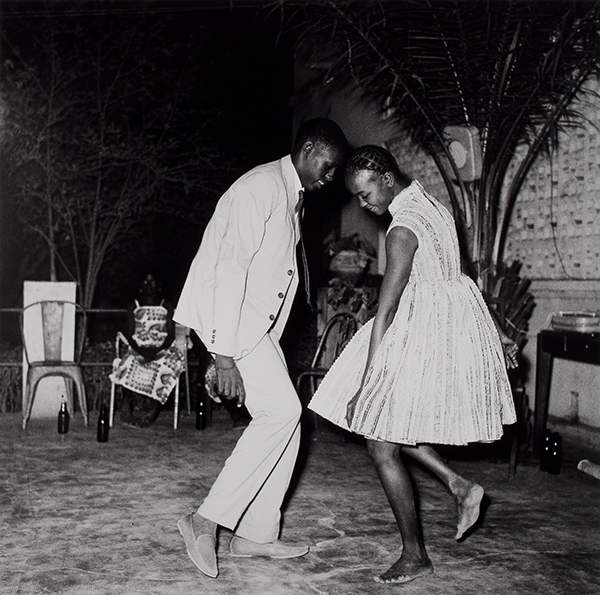

Source: Malick Sidibé, Nuit de Noël (Happy Club), 1963, Gelatin silver print. Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, Gift of the Estate of Lester and Betty Guttman, 2014.720. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

SHIFTING PERSPECTIVES. The Smart Museum at the University of Chicago will be displaying the exhibit “Not All Realisms” through June 4, 2023. The goal of the exhibit is to show the relationship between people and media in African countries during the 1960’s.

February 20, 2023

When we think of the 1960s we think of a fixed period, 10 years to be exact. When we think of photography, we think of photographic prints depicting real life events. We lose track of the photograph as a document, particularly in the age of social media.

But Leslie Wilson, guest curator of the Smart Museum at the University of Chicago, asks: Does that mean we shouldn’t take photographs? What is the potential and risk of capturing an image?

“Not All Realisms: Photography, Africa, and the long 1960s,” is the first self-organized exhibition examining African Art at the Smart Museum of Art, celebrating the intersection of photography and ideas. The exhibition will feature an estimated 60 photographic prints and run from Feb. 23-June 4.

Dr. Wilson says the exhibition will demonstrate the complexity of the 1960s and the relationship between viewers and the photograph.

She said, “I really wanted us to look at what people wanted out of the photographs they were making. How were they circulating them? How were they presenting them? Why were they making photographs?”

In addition to the photographic prints, the installation will feature over 130 publications from as early as the 1950s as well as contemporary works. The more recent examples reimagine and build upon the photographic techniques of the era.

“It became really interesting to me, in terms of ways the 1960s aren’t just a decade but bound up in all the ideas of that moment, ideas about liberation and ideas about representation,” Dr. Wilson said.

The exhibition will feature four sections “making matter,” serving as the foundation for the show; “before & after,” centering on juxtaposition; “us & not-us,” a reflection on viewers identification with art; and “again & again,” in which we see the 1960s imagery return in contemporary art.

‘Not All Realisms’ can represent a testament from the oppressed. It’s a refusal to silence themselves and let their oppressors control the narrative. — Dr. Leslie Wilson, guest curator of the Smart Museum

Dr. Wilson hopes these smaller sections will prompt the viewer to think critically about photographs and how they are portrayed.

“I wanted to think about these uneven histories and different kinds of experiences. Who’s finding their way to liberation which is very much mired in struggle,” Dr. Wilson said.

The idea of narrative and how the ideas of the 1960s continue to live on in the modern fight against oppression is an important theme in the exhibition.

“Actually, there’s a way that the ’60s kind of lives as unfinished business. We’re still trying to get to that place where we’re living in more equal societies, the gap between rich and poor has collapsed, children are having better outcomes,” Dr. Wilson said, “And thinking about the way it often exists as a beacon for more work to be done — a kind of hope.”

The title, “Not All Realisms” originates from the essay by American photographer Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive.” His commentary on Ernest Cole’s project, who is one of the many artists featured in this exhibition, examines the idea of realism in the hands of oppressors.

Dr. Wilson believes “Not All Realisms” can represent a testament from the oppressed. It’s a refusal to silence themselves and let their oppressors control the narrative.

“I started to read ‘Not All Realisms’ like a hashtag. Similar to the ‘Not all’ hashtags,” she said. “That’s how it got its name.”

Dr. Wilson says the constant battle we have with photographs is balancing their potentially problematic nature with the truths and stories they can reveal.

“I want viewers to hopefully think about what is missing and how we often use these as models for narrative- but we often leave a lot out,” Dr. Wilson said. “So how can we look and think critically about how we use images?”

“Not All Realisms” encourages the viewer to reevaluate their attitude toward the literal but simultaneously acknowledge that not all realisms represent untruths.

This story was updated Feb. 20 at 9:10 p.m. to correct the definition of “Not All Realisms: Photography, Africa, and the long 1960s.”