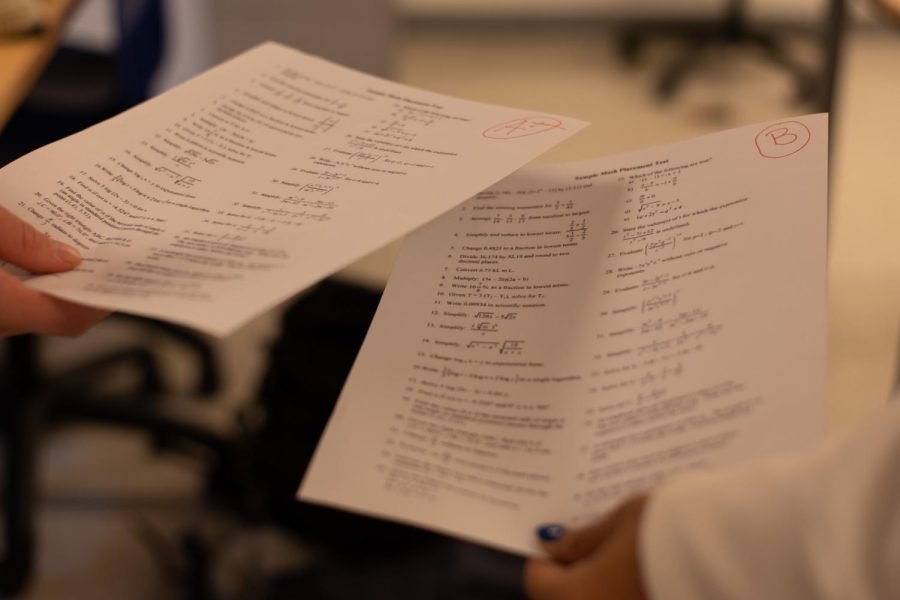

Comparison culture: Students feel need to compare grades despite teacher intervention

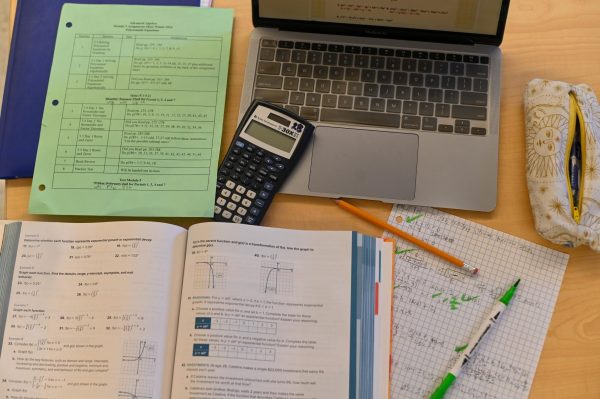

CONSTANTLY COMPARING: Although teachers have attempted to limit U-High’s strong emphasis on grades, the school’s high-achieving culture leads many students to constantly compare their grades with peers.

January 17, 2023

The rustling of paper sounds throughout the classroom as exams are handed back. Following almost immediately after comes chatter, slowly increasing in volume.

“What did you get?”

“How’d you do?”

“I totally flunked that.”

“Yesss!”

Most teachers at U-High forbid grade comparison, but it’s a difficult rule to enforce. It’s a chain reaction — one student might mention it to a friend, the nervous questions swiftly spreading through the room. Comparison of exam scores and report cards is just one branch of the overall culture around grades at U-High.

At a high-performing school that puts a lot of emphasis on academics and performance, there’s bound to be anxiety and dialogue about grades among students, but some think that discussing and comparing academic standing can be harmful, whether mentally or academically.

One of the reasons this might be an issue for U-High students is the feeling of discouragement when a student receives a worse score or grade than a classmate. This can, in some cases, lead to the student resigning themselves to continuing to do poorly, losing the energy and/or motivation to try harder. It can be not only demoralizing but embarrassing for students to find out their friends or classmates are doing better academically than they are, across the board or on one specific assignment or test.

Teachers recognize this issue, and many have their own thoughts about why it might exist.

“It’s the fear. The fear of not being able to do something, or not knowing how to do it, sometimes causes people to just resign themselves to this state as opposed to making an effort that puts aside fear,” Biology teacher Daniel Calleri said. “The fear gets in the way.”

Recently, high school English classes have switched to a “gradeless” policy, meaning that individual assignments have feedback and comments instead of scores or letter grades, though students still receive a letter grade on their final progress report. The goal of this policy is to refocus the attention of students in English class to developing their skills in reading and writing, and move it away from grades and scores.

“I think that when students only think about the grade without thinking about the feedback attached to it, which is actually the thing that tells them how to improve, you see less writing improvement,” English I teacher Shannon Barker said.

Some students, however, find that this policy causes anxiety regarding their current progress in the class.

“Grades help me see where I need to improve and where I’m doing well,” ninth grader Isolde LaCroix-Birdthistle said. “The ‘Met expectation’ and ‘Didn’t meet expectation’ grades are very vague.”

The nervous chatter is replaced by zipping backpacks as students pack up their binders, laptops, and graded exams. The shuffling of feet fills the room as the high schoolers file out into the hallway and depart for their next classes.